The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project was created in 2009 as a partnership between Zoo New England, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Houston Zoo, Smithsonian National Zoo, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Defenders of Wildlife to build captive populations of species at risk of extinction from the deadly amphibian chytrid fungus. Together we have built significant capacity for amphibian conservation in Pamama by contributing financial resources, involving zoo staff in field work to collect and care for endangered amphibians, training our Panamanian colleagues in state-of-the art animal care, veterinary care, pedigree management and record-keeping.

Since the project was established, Zoos have provided approximately $300K per year with a total investment of $2.7m in the project that leveraged additional support of $3.9m in grants from Miambiente, First Quantum Minerals (Cobre Panama), USAID, the National Science Foundation, SENACYT, National Geographic, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, the Morris Animal foundation and other private donors. First Quantum Minerals (Cobre Panama) has been our largest corporate contributor, providing approximately $450K per year with a total investment of $2.3m in the project.

Milestones

Endangered Frogs

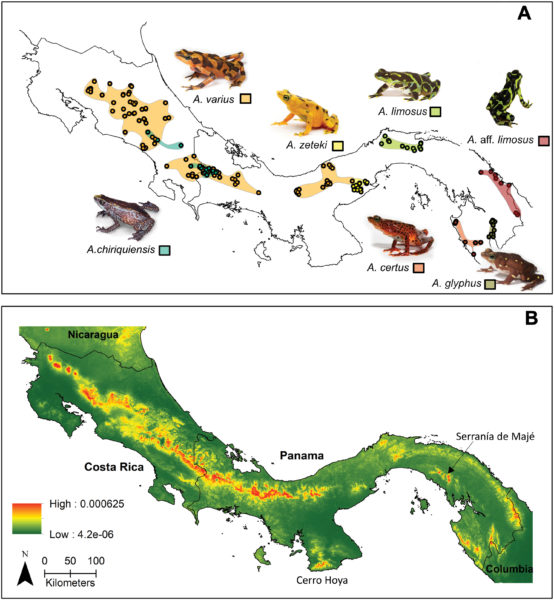

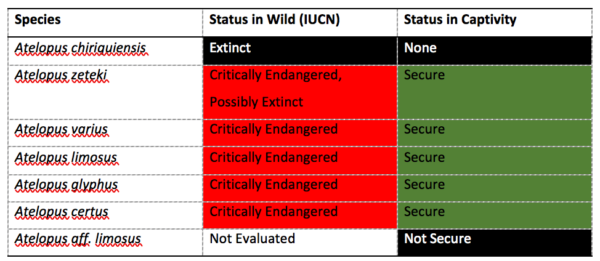

Established founding populations of 12 species of Panama’s most endangered frogs, including Panama’s iconic Panamanian Golden Frog. Reproduced all 12 species in captivity most of them bred in captivity for the first-time ever by project staff.

Capacity-Building

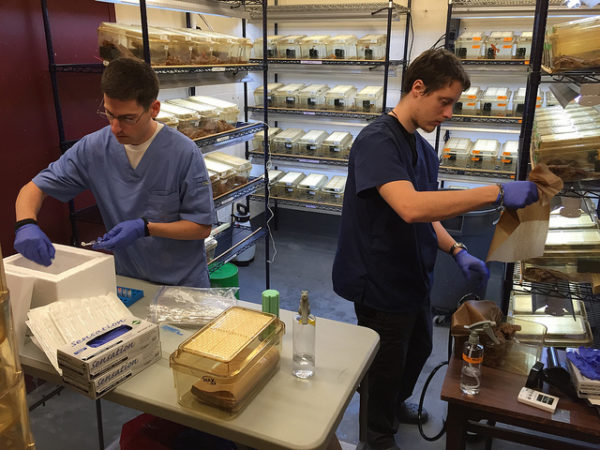

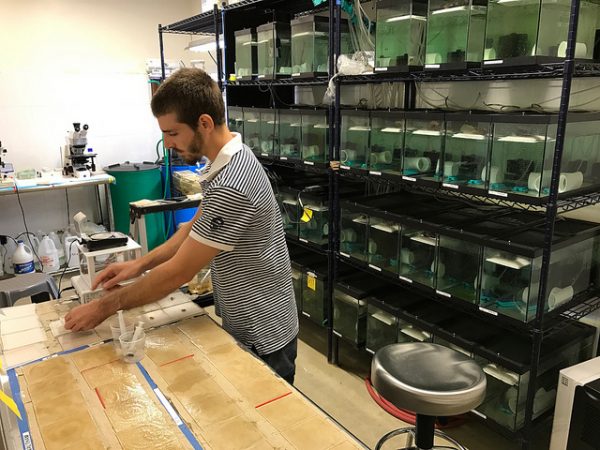

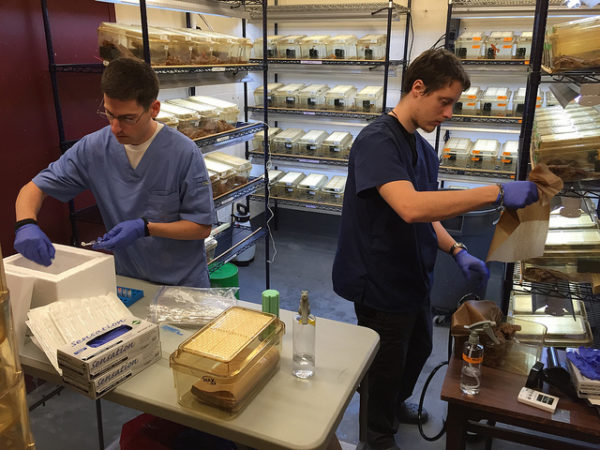

Constructed the Gamboa Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Center which is now the largest amphibian conservation breeding center in the world and trained a professional cadre of conservation staff to care for the animals.

Research

Established a world-class research program investigating the frog-killing chytrid fugus and searching for a cure for the disease. Conducting hormone stimulation research to improve captive reproduction. Continued publications of veterinary care, nutrition and husbandry of amphibians to improve knowledge to sustain captive amphibians.

Reintroductions

Conducted the first-ever reintroduction trials of amphibians to learn about the limiting factors how captive frogs transition back into the wild. This data will be used to inform future release strategies using adaptive management principles.

Education

Annual coordination of ‘Festival la Rana Dorada’ activities in Panama City, continued operation of fabulous frogs of Panama exhibition and the integrated informal schools’ curriculum.

Vision for the future

We need to continue to grow the captive amphibian populations to about 300 animals per species with even representation of founder animal genes as the primary assurance colony. This core captive population will safeguard against species’ extinction, and biological banking of gametes will help to ensure against unintended genetic bottlenecks in captivity. Surplus-bred animals will be used for further basic reintroduction research, breeding for disease-resistance, finding a cure for the amphibian chytrid fungus, and basic research that will ultimately be used to reestablish viable wild populations of these species.