Category Archives: ex-situ conservation

First Release Trial to Help Pave the Way for Reintroduction Programs for Critically Endangered Frogs

Ninety Limosa harlequin frogs (Atelopus limosus) bred in human care are braving the elements of the wild after Smithsonian scientists sent them out into the Panamanian rainforest as part of their first-ever release trial. The study, led by the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, aims to determine the factors that influence not only whether frogs survive the transition from human care to the wild, but whether they persist and go on to breed.

“Only by understanding the trials and tribulations of a frog’s transition from human care to the wild will we have the information we need to someday develop and implement successful reintroduction programs,” said Brian Gratwicke, international program coordinator for the rescue project and Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) amphibian conservation biologist. “Although we are not sure whether any of these individual frogs will make it out there, this release trial will give us the knowledge we need to tip the balance in favor of the frogs.”

The Limosa harlequin frogs released at the Mamoní Valley Preserve, have small numbered tags inserted under their skin so that researchers can tell individuals apart. The scientific team also gave each frog an elastomer toe marking that glows under UV light to easily tell this cohort of frogs apart from any future releases. Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation Ph.D. student Blake Klocke is currently monitoring the frogs daily at the site, collecting information about survivorship, dispersal, behavior and whether the warm micro-climate in the area provides any protection against disease.

The study is also looking at whether a “soft release” boosts the frogs’ ability to survive. Thirty of the newly released frogs spent a month at the site in cages, acclimating to their surroundings and foraging on leaf-litter invertebrates. Eight of these frogs, and eight that were released without the trial period, are wearing miniature radio transmitters that will give Klocke and team a chance to look at differences in survival and persistence between the two groups. The researchers also collected skin bacteria samples from the soft release frogs to measure changes during their transition from captivity to the wild.

“The soft release study allowed us to safely expose captive-bred frogs to a more balanced and varied diet, changing environmental conditions and diverse skin bacteria that can potentially increase their survival in nature,” said Angie Estrada, Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech and a member of the team leading the soft release, which was funded through a Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) grant and support from the National Science Foundation. “It allowed us to monitor health and overall body condition of the animals without the risk of losing the frogs right away to a hungry snake.”

Limosa harlequin frogs are especially sensitive to the amphibian chytrid fungus, which has pushed frog species to the brink of extinction primarily in Central America, Australia and the western United States. The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project brought a number of individuals into the breeding center between 2008 and 2010 as chytrid swept through their habitat. The Limosa harlequin frogs in this release trial are the first captive-bred generation of the species, and only part of the rescue project’s total insurance population for the species.

“After all the work involved in collecting founder individuals, learning to breed them, raising their tadpoles, producing all their food, and keeping these frogs healthy, the release trial marks a new, exciting stage in this project,” said Roberto Ibáñez, in-country director of the rescue project and STRI scientist. “These captive-bred frogs will now be exposed to their world, where predators and pathogens are ever-present in their environment. Their journey will help provide the key to saving not only their own species, but Panama’s other critically endangered amphibian species.”

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a project partnership between the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Houston Zoo, Zoo New England, the SCBI and STRI. This project received additional support from the Friends of the National Zoo, Holohil, The Woodtiger Fund, Mamoni Valley Preserve and Earth Train.

SCBI plays a leading role in the Smithsonian’s global efforts to save species from extinction and train future generations of conservationists. SCBI spearheads research programs at its headquarters in Front Royal, Va., the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and at field research stations and training sites worldwide. SCBI scientists tackle some of today’s most complex conservation challenges by applying and sharing what they learn about animal behavior and reproduction, ecology, genetics, migration and conservation sustainability.

First-Time Breeding of Frog Suggests Hope for Critically Endangered Species

When researchers discovered Craugastor evanesco in the rainforests of Panama, they called it the vanishing robber frog to signify just how quickly the deadly infectious amphibian disease chytridiomycosis had devastated its population. By the time the researchers had published about the new species in 2010, the vanishing robber frog had already disappeared from the park where they had discovered it.

Now, however, the vanishing robber frog may have a fighting chance at a future thanks to the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, which in December became the first program to breed the species in human care. After multiple attempts at breeding the species since 2015, a single pair has now produced one offspring—a success that has encouraged a cautious optimism that the rescue project can replicate the effort.

“A single individual doesn’t make a successful captive breeding program, but demonstrates that it can be done,” says Brian Gratwicke, an amphibian conservation biologist for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and rescue project international coordinator. “Every journey begins with the first step and this is a critical first step, not just for this species, but potentially for other endangered amphibians with similar reproductive needs.”

The rescue project, a world-class amphibian center run by SCBI and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, currently has a founding population of 20 males and 20 females of the vanishing robber frog. Conservationists collected the frogs from a lowland site in central Panama where the rescue project is working with the support of Minera Panama S.A. to conserve amphibians in the area. But bringing a new and critically endangered species into human care requires learning its own unique husbandry and reproductive needs before it blinks out of existence—sometimes resulting in insurmountable challenges.

“Piecing together a species’ natural history with artificial systems, we can recreate to the best of our abilities an environment where the animals feel comfortable enough to breed,” said Heidi Ross, STRI’s director of El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, whose expertise and persistence led to the successful first-time breeding of the species. “If we can get them to this point, to become sexually active in our artificial habitat, then we can simply tweak the system based on what worked, what did not work, and what materials are at our disposal. What we arduously do day in and day out is make sure we are providing the basic needs to the animals so that they help us help them from going extinct in the wild.”

The Craugastor group of frogs has a unique reproductive system called direct development—they bury eggs in wet sand and fully formed miniature adults hatch from the eggs. Understanding the frogs’ reproductive cues, special dietary needs and how to emulate the natural environment is essential to successful breeding, Ross says.

“Given the current difficult situation for amphibians in our region, this project represents scientific and biological hope, not only for this species of frog, but also for the recovery of Craugastor evanesco within its distribution range,” said Blanca Araúz, biologist and biodiversity superintendent of Minera Panamá. “As one of the species of interest for our project Cobre Panamá, its reproduction in captivity is important. Because the deadly infectious disease acts fast, experienced scientists can control the infection in these frogs and breed them under better conditions.”

Although scientists are still occasionally finding individual vanishing robber frogs in the field, they have not found a viable, self-sustaining population. Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines of amphibian species worldwide. This particular group of frogs in the Craugastor rugulosus series are particularly susceptible to chytridiomycosis with three closely related species in Panama having disappeared, putting extra pressure on ensuring the survival of Craugastor evanesco.

Although scientists are still occasionally finding individual vanishing robber frogs in the field, they have not found a viable, self-sustaining population. Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines of amphibian species worldwide. This particular group of frogs in the Craugastor rugulosus series are particularly susceptible to chytridiomycosis with three closely related species in Panama having disappeared, putting extra pressure on ensuring the survival of Craugastor evanesco.

“It’s all a learning curve,” Gratwicke says. “I’m hopeful that we’ll be able to replicate this breeding event to develop a sustainable breeding program. If we can do that, we’ll be able to get this species back out in the wild as soon as we figure out how to safely do so. If we can do that, it’ll be time to celebrate.”

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a partnership between the Houston Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, SCBI and STRI.

Earth optimism: Frogs

What’s Working in Conservation

The global conservation movement has reached a turning point. We have documented the fast pace of habitat loss, the growing number of endangered and extinct species, and the increasing speed of global climate change. Yet while the seriousness of these threats cannot be denied, there are a growing number of examples of improvements in the health of species and ecosystems, along with benefits to human well-being, thanks to our conservation actions. Earth Optimism is a global initiative that celebrates a change in focus from problem to solution, from a sense of loss to one of hope, in the dialogue about conservation and sustainability.

Dr Brian Gratwicke will present the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project on Saturday April 22 5:15pm on the panel Science on the Edge

Love potion for frogs

Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution and partners have published a paper that optimizes sperm collection protocols from the critically endangered Panamanian Golden Frog Atelopus zeteki. It also improves our understanding of reproduction in endangered harlequin frogs. The research, to be published published 15 March 2017, in Theriogenology, was conducted by Dr. Gina DellaTogna, a Panamanian biologist who studied this charismatic animal at the National Zoological Park in Washington DC. The study characterizes the dose-response patterns for several artificial hormone treatments and describes the sperm morphology for the first time in this species.

“This study is important, because it contributes towards the basic understanding of reproduction of a highly endangered group of frogs in Latin America,” said DellaTogna, who performed the experiments for her PhD at the University of Maryland. “This study has already helped us to solve critical reproduction problems in captive Atelopus collections in Panama and allowed us to repeatedly collect high-quality sperm samples for genome resource banking at any time of the year, without harming the frogs.”

“Basic reproductive research is something that has yielded huge conservation dividends for the successful care and management of other endangered species like Pandas and Black Footed Ferrets,” said Pierre Comizzoli, a co-author of the paper and reproduction specialist at the National Zoo. “Gina’s research opens the door to develop methods like sperm freezing and storage to preserve the long term genetic integrity and diversity in small populations.”

The research is particularly relevant to current amphibian conservation efforts in Panama where the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has captive-breeding colonies of five species of Atelopus that are threatened with extinction from the deadly fungal disease chytridiomycosis.

Roberto Ibáñez, and Gina DellaTogna working on hormonal stimulation of frogs at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project

“Successful reproduction is key to any captive assurance program,” said Roberto Ibáñez, the director of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation project at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. “Gina has already begun applying what she has learned to successfully help us to produce offspring from four other endangered harlequin frog species. I hope that she will eventually extend it to species with different modes of reproduction that are also difficult to breed”.

The research was made possible with assistance from the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore who manage the Golden Frog Species Survival Plan. Funding was provided from the Panamanian Government’s Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (SENACYT), The WoodTiger Fund, the Smithsonian Endowment for Science and the University of Ottawa Research Chairs Program.

Della Togna G, Trudeau VL, Gratwicke B, Evans M, Augustine L, Chia H, Bronikowski EJ, Murphy JB, Comizzoli P. 2017 Effects of hormonal stimulation on the concentration and quality of excreted spermatozoa in the critically endangered Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki). Theriogenology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.12.033

Science to the Rescue in the #FightForFrogs

Gina Della Togna with a Panamanian golden frog, a beloved species at the center of her research. (Photo by Pei-Chih Lee, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

When SCBI conservation biologist Brian Gratwicke started the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project with partners in 2009, it was a mad dash to find and collect frogs representing the very last best hope for their species, rapidly vanishing at the hands of an amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd) that causes a disease called chytridiomycosis.

If that was the opening chapter of the rescue project’s story, seven years later the story reads like a manuscript for an initiative set up to be among the most successful comprehensive conservation projects to date.

Today the rescue project has provided a stable safe haven for 12 of the most imperiled Panamanian frog species, requiring keepers to learn the complex husbandry, behavior and reproductive physiology unique to each individual species. In the meantime, rescue project scientists are making strides in developing and refining assisted reproduction protocols, while also conducting experiments in a resolute search for a cure for Bd.

“We are entering a new phase,” Gratwicke says. “We’ve brought together some of the world’s leading animal husbandry experts, veterinarians, reproductive biologists, disease ecologists and herpetologists. With all of the talented scientific minds working on this one, we have great hope that we may someday be able to return these species safely to their home in the wild.”

Searching for a Cure

Things in Matt Becker’s lab can sometimes get a bit…strange. Take, for instance, an experiment the SCBI postdoctoral researcher conducted a year ago with unexpected results. Becker’s research focuses on the use of probiotics—or beneficial bacteria—to help frogs fight off Bd. Last year Becker applied five different probiotics with anti-fungal properties to the skin of five groups of Panamanian golden frogs, hoping to discover which probiotic gives them an effective shield against the pathogen.

Matt Becker prepares-probiotic baths. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

What he found surprised him. In past experiments, the probiotics were ineffective and all of the frogs died after the researchers infected them with Bd. This time, though, about 25 percent of the individuals survived. And those surviving frogs didn’t come from just one group with one kind of probiotics, but from every group, even the one that had been infected with Bd without a probiotic protectant.

So Becker and Gratwicke needed to determine what it was that the frogs did have in common to help them fight the disease. They started by looking at the frogs’ microbial community, or the complex community of bacteria on the skin. All of the frogs that survived had a greater abundance of specific bacteria on their skin.

In June of this year, the team launched a new experiment, this time using frogs from the Species Survival Plan collection at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore that have similar abundances and types of bacteria as those that survived last year. The researchers have given the frogs a cocktail of eight bacteria that seem to strongly ward off Bd.

Looking at which immune system genes turn on or off to fight off a chytrid infection can help scientists discover why some frogs aren’t as susceptible. (Photo by Mehgan Murphy, Smithsonian’s National Zoo)

“At the start of every experiment, you’re really optimistic,” says Becker, who has been working on golden frog probiotics since 2007. “It’s been a great journey and we’re really learning a lot about golden frogs and how chytrid affects these guys. Every little bit of information really goes a long way for the conservation of this species and similar species.”

For the first time during a probiotics study on frogs, the researchers will also be looking at the gene expression—or combination of genes in an individual frog that gets turned on or turned off—while the frog mounts an immune response to fight off Bd.

“We’re throwing everything we’ve got at this,” Becker says. “We want to be able to use these tools to determine which frogs in the overall captive population share those same strengths—either their microbial community or gene expression—that keep them alive. There are so many questions we need to answer, but through the scientific process, we’re getting there.”

Frogs for the Future

While Becker is focused on getting frogs safely back into the wild, this goal is only possible if there are actually future generations of frogs to release into the wild. That’s where Smithsonian researcher and Panamanian native Gina Della Togna comes in.

Gina Della Togna in the lab. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

Della Togna is working on a number of complex assisted reproduction techniques for Panamanian frog species. She is the first scientist to develop protocols for extracting and freezing sperm from the Panamanian golden frog, a species that is extinct in the wild and a cultural icon in her home country. Scientists could someday use the sperm to infuse populations with additional genetic diversity, key to a species’ overall health.

“When we started, we didn’t know anything about anything,” Della Togna says. “We needed to learn which hormones at what concentrations to use, how to keep the sperm alive long enough to freeze it and the best techniques to freeze it so that the sperm is viable when we thaw it, even years later. It was a challenge, but I love a good challenge.”

Now Della Togna is working on developing similar protocol for other rescue project species, including the mountain harlequin frog, Pirre harlequin frog, variable harlequin frog, limosa harlequin frog and the rusty robber frog. In the future, she plans to get out into the field to capture genetic lineages from frogs in the wild. As she continues to perfect these protocols, Della Togna also aims to collect eggs from female Panamanian golden frogs to use for artificial fertilization with the frozen sperm. And most recently in Panama, she successfully applied a hormone treatment to help six pairs of the limosa harlequin frog and Pirre harlequin frogs breed that hadn’t laid eggs before.

“Breeding frogs is the fundamental step to sustaining captive populations and growing the numbers for release trials,” Gratwicke says. “Gina’s work is of huge applied value to us because we have some very challenging species to breed, and hormone dosing may help us to get them to cycle reproductively, even if we can’t figure out the external reproduction cues.”

For Della Togna, Gratwicke and Becker, the goal is the same: to give these unique species a fighting chance against Bd.

“If these frogs go extinct, nothing can replace them,” Della Togna says. “They are important to the ecosystem and essential to our planet’s equilibrium. There’s no doubt that we’re responsible for getting them back to where they belong.”

From now until the end of August, you can help us #FightForFrogs! Our generous sponsor Golden Frog—a global online services provider with a terrific name—will match donations to the rescue project up to $20,000, helping us raise money critical to our fight for frogs. Your donations during the Fight for Frogs campaign will buy us equipment to care for the frogs in the rescue pods, help us continue to conduct experiments to find a cure, ensure crucial breakthroughs, and ultimately one day see the return of these incredible species to their home in the wild.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a project partnership between the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Houston Zoo, Zoo New England and Smithsonian Institution. You can follow the Fight for Frogs campaign on Twitter using the #FightForFrogs hashtag or on the rescue project’s Facebook page.

New Amphibian Study Helps Smithsonian Scientists Prioritize Frogs at Risk of Extinction

Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution and partners have published a paper that will help them save Panamanian frog species from extinction due to a deadly fungal disease called Chytridiomycosis (chytrid). The study, which was published Jan. 4 in Animal Conservation, draws on the expertise of amphibian biologists and scientists the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project to mathematically determine which frog species have the best probability of escaping extinction with the rescue project’s help.

Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution and partners have published a paper that will help them save Panamanian frog species from extinction due to a deadly fungal disease called Chytridiomycosis (chytrid). The study, which was published Jan. 4 in Animal Conservation, draws on the expertise of amphibian biologists and scientists the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project to mathematically determine which frog species have the best probability of escaping extinction with the rescue project’s help.

“We don’t want to arbitrarily decide which species lives and which species don’t, nor do we want to waste our time on species that don’t need our help,” said Brian Gratwicke, co-author on the paper and international coordinator of the rescue project out of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. “This study took into account the differences in opinions among amphibian experts in Panama and found consensus in a systematic away. This has allowed us to focus on the species where we have the best chance of making a difference.”

The study also found that eight Panamanian species are likely now extinct in the wild due to disease-related declines. About 80 of Panama’s frog species were too rare for conservationists to prioritize their need for help or the likelihood of successful rescue. The new prioritization scheme, however, will allow the scientists to adapt to new information as it becomes available.

“Over the years, several frog populations—and even species—have vanished or nearly vanished from Panama,” said Roberto Ibáñez, the in-country director of the rescue project at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, “Unfortunately, it is impossible to save them all through conservation programs. With this study, we can focus our limited resources on those species that we are more likely to find in the wild and breed in captivity, while we simultaneously look for a way to manage chytrid.”

Since 2009, the rescue project has been building and maintaining insurance populations of frog species susceptible to chytrid, bringing small groups into captivity to breed as the species crashes in the wild. For each of Panama’s 214 known frog species, the paper’s authors asked amphibian experts to determine the probability that: 1) the rescue project could locate an adequate founding population (20 males and 20 females), 2) the rescue project could successfully breed the species and 3) without the rescue project’s help, the species would go extinct.

While most of the rescue project’s original priority species ranked high based on the new prioritization scheme, the conservationists have already started making some changes. They have determined that the likelihood of successfully breeding La Loma tree frogs (Hyloscirtus colymba) is low and they are instead shifting resources to the recently discovered Craugastor evanesco and the Rusty robber frog (Strabomantis bufoniformis), both of which came up as high priorities.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a project partnership between the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Houston Zoo, Zoo New England and Smithsonian Institution.

Golden frogs with unique communities of skin bacteria survive exposure to frog-killing fungus

Chytridiomycosis is an amphibian disease that has wiped out populations of many frog species around the world, including the charismatic Panamanian golden frog, which now exists only in captivity in the United States and Panama.

Research published this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society found unique communities of skin bacteria on golden frogs that survived chytridiomycosis. The original experiment was designed to test the idea that antifungal probiotic bacteria may be used to prevent chytridiomycosis in captive golden frogs. Approximately 25 percent of the golden frogs eventually cleared infection, but their survival was not associated with the probiotic treatment, rather it was associated with bacteria that were present on their skin prior to the start of the experiment. In fact, the probiotic antifungal bacteria did not appear to establish on the golden frog skin at all.

Matthew Becker, a fellow at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute who conducted the experiment as part of his PhD research at Virginia Tech University, says it is unclear why the microbes did not linger on the skin, but he thinks that the way he treated the frogs – with a high dose of bacteria for a short duration – may be part of the reason.

Matthew Becker, a fellow at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute who conducted the experiment as part of his PhD research at Virginia Tech University, says it is unclear why the microbes did not linger on the skin, but he thinks that the way he treated the frogs – with a high dose of bacteria for a short duration – may be part of the reason.

“I think identifying alternative probiotic treatment methods that optimize dosages and exposure times will be key for moving forward with the use of probiotics to mitigate chytridiomycosis,” Becker said.

Brian Gratwicke, amphibian conservation biologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute where the experiment was conducted, says that he was disappointed that they did not find a ‘silver bullet’ to cure chytridiomycosis in this species, but noted that the results do advance our understanding of this disease.

“Previous experiments found that golden frogs are highly susceptible to chytridiomycosis, so any survival is cause for hope,” said Reid Harris, director of disease mitigation at the Amphibian Survival Alliance. “The tricky piece is figuring out the survival mechanism, and this exciting research gives some new insights in that direction.”

This research also provides additional support for the importance of symbiotic microbes, or the ‘microbiome,’ for the health of their hosts, ranging from sponges and corals to humans.

“In all multi-cellular organisms, we have suites of microbes performing critical functions for their hosts, and the same appears to be true for golden frogs,” said Lisa Belden, who supervised the study at Virginia Tech University.

The team, led by Becker, now plans to determine if this study is repeatable by investigating whether the golden frog’s skin microbiota can predict the susceptibility to chytridiomycosis. They will also investigate whether the bacteria associated with the surviving frogs from this study can be used as a probiotic treatment to prevent infections of golden frogs without a ‘protective’ microbiota.

“The ultimate goal of this research is to identify a method to establish healthy populations of golden frogs in their native habitat, despite the presence of chytridiomycosis in the environment,” Becker said.

Citation: Matthew H. Becker, Jenifer B. Walke, Shawna Cikanek, Anna E. Savage, Nichole Mattheus, Celina N. Santiago, Kevin P. C. Minbiole, Reid N. Harris, Lisa K. Belden, Brian Gratwicke (2015) Composition of symbiotic bacteria predicts survival in Panamanian golden frogs infected with a lethal fungus. Proc. R. Soc. B: 2015 282 20142881; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2881. Published 18 March 2015

Newly Described Poison Dart Frog Hatched for the First Time in Captivity

The first captive-bred Andinobates geminisae at the Gamboa Amphibian Research and Conservation Center. Photo by Jorge Guerrel, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) scientists working as part of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project hatched the first Andinobates geminisae froglet born in captivity. The tiny dart frog species only grows to 14 millimeters and was first collected and described last year from a small area in central Panama. Scientists collected two adults to evaluate the potential for maintaining the species in captivity as an insurance population.

“There is a real art to learning about the natural history of an animal and finding the right set of environmental cues to stimulate successful captive breeding,” said Brian Gratwicke, amphibian conservation biologist at SCBI and director of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project. “Not all amphibians are easy to breed in captivity, so when we do breed a species for the first time in captivity it is a real milestone for our project and a cause for celebration.”

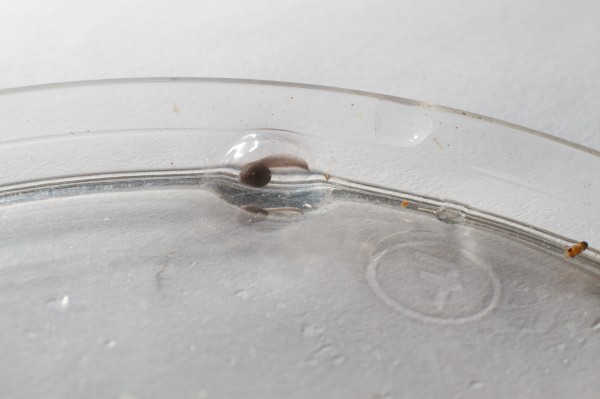

Scientists simulated breeding conditions for the adult frogs in a small tank. The frogs laid an egg on a bromeliad leaf, which scientists transferred to a moist petri dish. After 14 days, the tadpole hatched. Scientists believe adult A. geminisae frogs may provide their eggs and tadpoles with parental care, which is not uncommon for dart frogs, but they have not been able to determine if that is the case. In the wild, one of the parents likely transports the tadpole on his or her back to a little pool of water, usually inside a tree or on a bromeliad leaf.

After the tadpole hatched, scientists moved it from the petri dish to a small cup of water, mimicking the small pools available in nature. On a diet of fish food, the tadpole successfully metamorphosed into a froglet after 75 days and is now the size of a mature adult.

Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project scientists are unsure if A. geminisae is susceptible to the amphibian-killing chytrid fungus. However, since it is only found in a small area of Panama and is dependent on primary rain forests, which are under pressure from agricultural conversion, they have identified it as a conservation-priority species.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project breeds endangered species of frogs in Gamboa, Panama and El Valle, Panama. The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a partnership between the Houston Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, SCBI and STRI. This study was supported by Minera Panama.

Researchers develop new method to test an amphibian’s susceptibility to the deadly amphibian chytrid fungus.

This new method could help us to test out new probiotic therapies. It can predict a captive-bred frog’s survival from exposure to chytrid fungus, without ever having to expose them to it experimentally.

Researchers at the University of Boulder Colorado, University of Zurich and Copenhagen University have developed a new method to predict how susceptible an amphibian is to a frog-killing fungus wiping out amphibians all over the world. The test looks at the antifungal properties of skin mucus that contains skin bacteria and chemicals secreted by the frog itself. Together the interactions between the skin bacteria and chemical secreted from glands on the frog skin are the frog’s first line of defense against skin disease.

Their paper, just published in PLOS One, sampled 8,500 frogs across Europe. They found that antifungal properties of the mucus were related to the prevalence of amphibian chytrid infection in natural populations. They found that when they experimentally exposed frogs to the chytrid fungus in a lab that they could predict survival of frogs based on an independent mucus sample. The researchers also found that when they added beneficial skin bacteria to the frogs that the anti-fungal properties of the skin were improved.

This study may help us to develop tools that we could use to reintroduce frogs back into areas affected by the frog-killing fungus, including Panama. “We have all these amphibians in captivity now, like the golden frog in Panama, a really beautiful species that is now extinct in the wild,” said Douglas Woodhams, a postdoctoral researcher at CU-Boulder and lead author of the paper. “We want to be able to reintroduce them, but the pathogen that attacked them is still out there,” he said. “Now we can determine what probiotic treatment might work best to protect the frogs without infecting them with the pathogen and seeing how many die.”

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi/10.1371/journal.pone.0096375