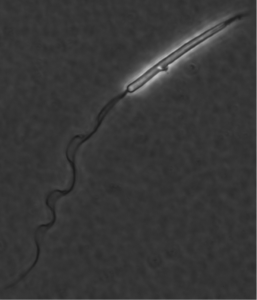

Chytridiomycosis is an amphibian disease that has wiped out populations of many frog species around the world, including the charismatic Panamanian golden frog, which now exists only in captivity in the United States and Panama.

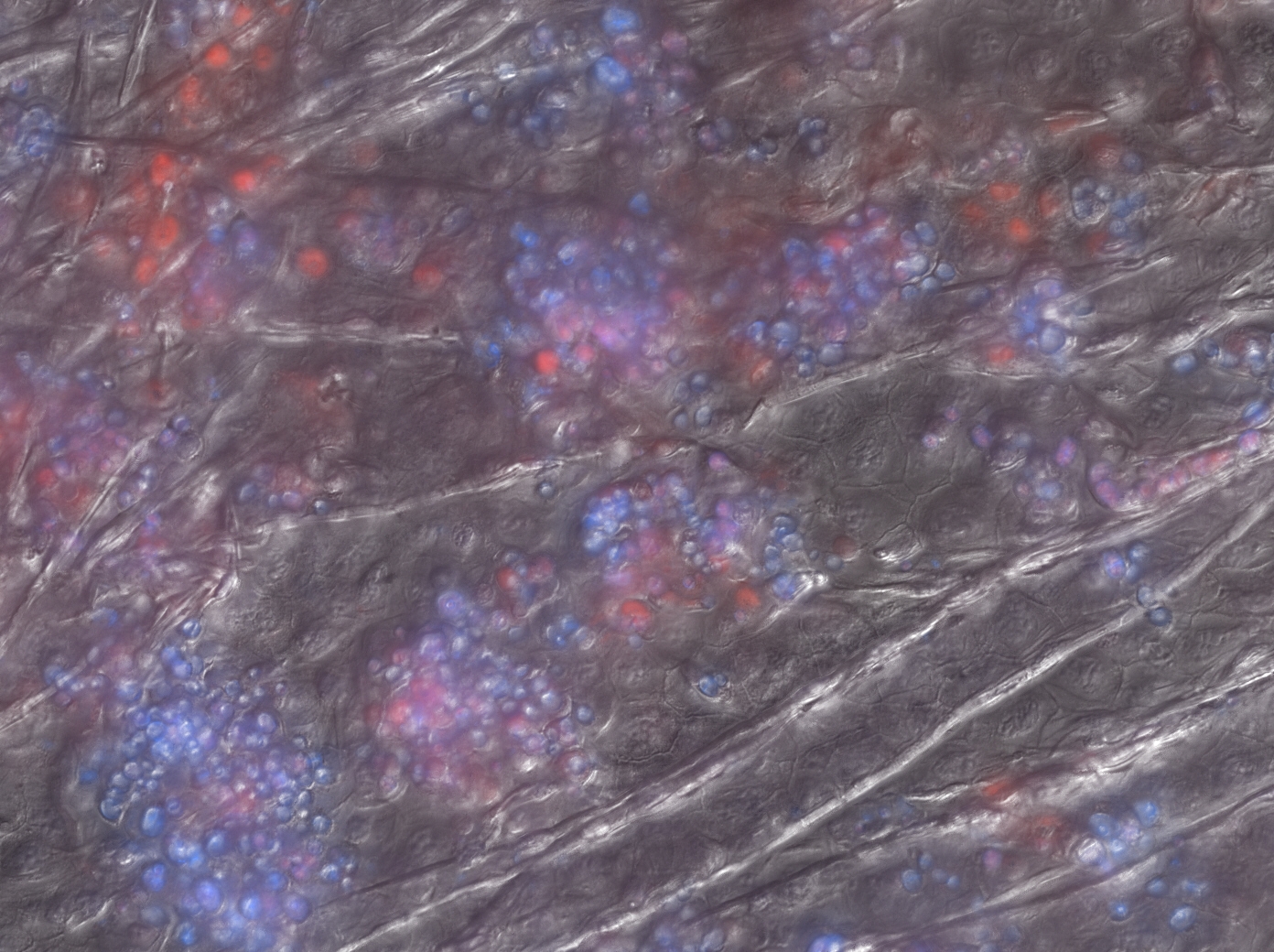

Research published this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society found unique communities of skin bacteria on golden frogs that survived chytridiomycosis. The original experiment was designed to test the idea that antifungal probiotic bacteria may be used to prevent chytridiomycosis in captive golden frogs. Approximately 25 percent of the golden frogs eventually cleared infection, but their survival was not associated with the probiotic treatment, rather it was associated with bacteria that were present on their skin prior to the start of the experiment. In fact, the probiotic antifungal bacteria did not appear to establish on the golden frog skin at all.

Matthew Becker, a fellow at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute who conducted the experiment as part of his PhD research at Virginia Tech University, says it is unclear why the microbes did not linger on the skin, but he thinks that the way he treated the frogs – with a high dose of bacteria for a short duration – may be part of the reason.

Matthew Becker, a fellow at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute who conducted the experiment as part of his PhD research at Virginia Tech University, says it is unclear why the microbes did not linger on the skin, but he thinks that the way he treated the frogs – with a high dose of bacteria for a short duration – may be part of the reason.

“I think identifying alternative probiotic treatment methods that optimize dosages and exposure times will be key for moving forward with the use of probiotics to mitigate chytridiomycosis,” Becker said.

Brian Gratwicke, amphibian conservation biologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute where the experiment was conducted, says that he was disappointed that they did not find a ‘silver bullet’ to cure chytridiomycosis in this species, but noted that the results do advance our understanding of this disease.

“Previous experiments found that golden frogs are highly susceptible to chytridiomycosis, so any survival is cause for hope,” said Reid Harris, director of disease mitigation at the Amphibian Survival Alliance. “The tricky piece is figuring out the survival mechanism, and this exciting research gives some new insights in that direction.”

This research also provides additional support for the importance of symbiotic microbes, or the ‘microbiome,’ for the health of their hosts, ranging from sponges and corals to humans.

“In all multi-cellular organisms, we have suites of microbes performing critical functions for their hosts, and the same appears to be true for golden frogs,” said Lisa Belden, who supervised the study at Virginia Tech University.

The team, led by Becker, now plans to determine if this study is repeatable by investigating whether the golden frog’s skin microbiota can predict the susceptibility to chytridiomycosis. They will also investigate whether the bacteria associated with the surviving frogs from this study can be used as a probiotic treatment to prevent infections of golden frogs without a ‘protective’ microbiota.

“The ultimate goal of this research is to identify a method to establish healthy populations of golden frogs in their native habitat, despite the presence of chytridiomycosis in the environment,” Becker said.

Citation: Matthew H. Becker, Jenifer B. Walke, Shawna Cikanek, Anna E. Savage, Nichole Mattheus, Celina N. Santiago, Kevin P. C. Minbiole, Reid N. Harris, Lisa K. Belden, Brian Gratwicke (2015) Composition of symbiotic bacteria predicts survival in Panamanian golden frogs infected with a lethal fungus. Proc. R. Soc. B: 2015 282 20142881; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2881. Published 18 March 2015