Category Archives: Rescue

Building an Amphibian Ark and Searching for a Cure for the Amphibian Chytrid Fungus

Recorded talk by Dr. Brian Gratwicke, international coordinator of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project presented as part of the virtual Golden Frog Festival for 2020.

First-Time Breeding of Frog Suggests Hope for Critically Endangered Species

When researchers discovered Craugastor evanesco in the rainforests of Panama, they called it the vanishing robber frog to signify just how quickly the deadly infectious amphibian disease chytridiomycosis had devastated its population. By the time the researchers had published about the new species in 2010, the vanishing robber frog had already disappeared from the park where they had discovered it.

Now, however, the vanishing robber frog may have a fighting chance at a future thanks to the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, which in December became the first program to breed the species in human care. After multiple attempts at breeding the species since 2015, a single pair has now produced one offspring—a success that has encouraged a cautious optimism that the rescue project can replicate the effort.

“A single individual doesn’t make a successful captive breeding program, but demonstrates that it can be done,” says Brian Gratwicke, an amphibian conservation biologist for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and rescue project international coordinator. “Every journey begins with the first step and this is a critical first step, not just for this species, but potentially for other endangered amphibians with similar reproductive needs.”

The rescue project, a world-class amphibian center run by SCBI and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, currently has a founding population of 20 males and 20 females of the vanishing robber frog. Conservationists collected the frogs from a lowland site in central Panama where the rescue project is working with the support of Minera Panama S.A. to conserve amphibians in the area. But bringing a new and critically endangered species into human care requires learning its own unique husbandry and reproductive needs before it blinks out of existence—sometimes resulting in insurmountable challenges.

“Piecing together a species’ natural history with artificial systems, we can recreate to the best of our abilities an environment where the animals feel comfortable enough to breed,” said Heidi Ross, STRI’s director of El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, whose expertise and persistence led to the successful first-time breeding of the species. “If we can get them to this point, to become sexually active in our artificial habitat, then we can simply tweak the system based on what worked, what did not work, and what materials are at our disposal. What we arduously do day in and day out is make sure we are providing the basic needs to the animals so that they help us help them from going extinct in the wild.”

The Craugastor group of frogs has a unique reproductive system called direct development—they bury eggs in wet sand and fully formed miniature adults hatch from the eggs. Understanding the frogs’ reproductive cues, special dietary needs and how to emulate the natural environment is essential to successful breeding, Ross says.

“Given the current difficult situation for amphibians in our region, this project represents scientific and biological hope, not only for this species of frog, but also for the recovery of Craugastor evanesco within its distribution range,” said Blanca Araúz, biologist and biodiversity superintendent of Minera Panamá. “As one of the species of interest for our project Cobre Panamá, its reproduction in captivity is important. Because the deadly infectious disease acts fast, experienced scientists can control the infection in these frogs and breed them under better conditions.”

Although scientists are still occasionally finding individual vanishing robber frogs in the field, they have not found a viable, self-sustaining population. Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines of amphibian species worldwide. This particular group of frogs in the Craugastor rugulosus series are particularly susceptible to chytridiomycosis with three closely related species in Panama having disappeared, putting extra pressure on ensuring the survival of Craugastor evanesco.

Although scientists are still occasionally finding individual vanishing robber frogs in the field, they have not found a viable, self-sustaining population. Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines of amphibian species worldwide. This particular group of frogs in the Craugastor rugulosus series are particularly susceptible to chytridiomycosis with three closely related species in Panama having disappeared, putting extra pressure on ensuring the survival of Craugastor evanesco.

“It’s all a learning curve,” Gratwicke says. “I’m hopeful that we’ll be able to replicate this breeding event to develop a sustainable breeding program. If we can do that, we’ll be able to get this species back out in the wild as soon as we figure out how to safely do so. If we can do that, it’ll be time to celebrate.”

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a partnership between the Houston Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, SCBI and STRI.

Science to the Rescue in the #FightForFrogs

Gina Della Togna with a Panamanian golden frog, a beloved species at the center of her research. (Photo by Pei-Chih Lee, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

When SCBI conservation biologist Brian Gratwicke started the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project with partners in 2009, it was a mad dash to find and collect frogs representing the very last best hope for their species, rapidly vanishing at the hands of an amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd) that causes a disease called chytridiomycosis.

If that was the opening chapter of the rescue project’s story, seven years later the story reads like a manuscript for an initiative set up to be among the most successful comprehensive conservation projects to date.

Today the rescue project has provided a stable safe haven for 12 of the most imperiled Panamanian frog species, requiring keepers to learn the complex husbandry, behavior and reproductive physiology unique to each individual species. In the meantime, rescue project scientists are making strides in developing and refining assisted reproduction protocols, while also conducting experiments in a resolute search for a cure for Bd.

“We are entering a new phase,” Gratwicke says. “We’ve brought together some of the world’s leading animal husbandry experts, veterinarians, reproductive biologists, disease ecologists and herpetologists. With all of the talented scientific minds working on this one, we have great hope that we may someday be able to return these species safely to their home in the wild.”

Searching for a Cure

Things in Matt Becker’s lab can sometimes get a bit…strange. Take, for instance, an experiment the SCBI postdoctoral researcher conducted a year ago with unexpected results. Becker’s research focuses on the use of probiotics—or beneficial bacteria—to help frogs fight off Bd. Last year Becker applied five different probiotics with anti-fungal properties to the skin of five groups of Panamanian golden frogs, hoping to discover which probiotic gives them an effective shield against the pathogen.

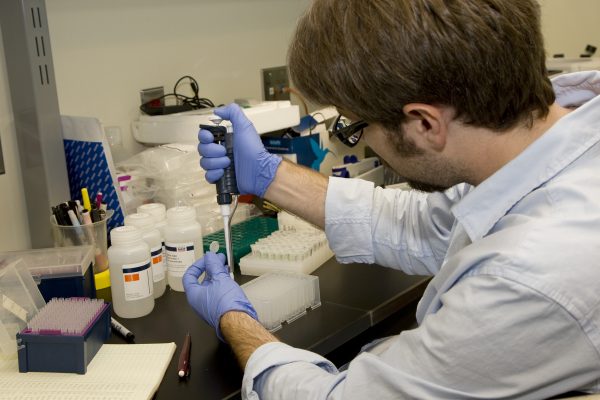

Matt Becker prepares-probiotic baths. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

What he found surprised him. In past experiments, the probiotics were ineffective and all of the frogs died after the researchers infected them with Bd. This time, though, about 25 percent of the individuals survived. And those surviving frogs didn’t come from just one group with one kind of probiotics, but from every group, even the one that had been infected with Bd without a probiotic protectant.

So Becker and Gratwicke needed to determine what it was that the frogs did have in common to help them fight the disease. They started by looking at the frogs’ microbial community, or the complex community of bacteria on the skin. All of the frogs that survived had a greater abundance of specific bacteria on their skin.

In June of this year, the team launched a new experiment, this time using frogs from the Species Survival Plan collection at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore that have similar abundances and types of bacteria as those that survived last year. The researchers have given the frogs a cocktail of eight bacteria that seem to strongly ward off Bd.

Looking at which immune system genes turn on or off to fight off a chytrid infection can help scientists discover why some frogs aren’t as susceptible. (Photo by Mehgan Murphy, Smithsonian’s National Zoo)

“At the start of every experiment, you’re really optimistic,” says Becker, who has been working on golden frog probiotics since 2007. “It’s been a great journey and we’re really learning a lot about golden frogs and how chytrid affects these guys. Every little bit of information really goes a long way for the conservation of this species and similar species.”

For the first time during a probiotics study on frogs, the researchers will also be looking at the gene expression—or combination of genes in an individual frog that gets turned on or turned off—while the frog mounts an immune response to fight off Bd.

“We’re throwing everything we’ve got at this,” Becker says. “We want to be able to use these tools to determine which frogs in the overall captive population share those same strengths—either their microbial community or gene expression—that keep them alive. There are so many questions we need to answer, but through the scientific process, we’re getting there.”

Frogs for the Future

While Becker is focused on getting frogs safely back into the wild, this goal is only possible if there are actually future generations of frogs to release into the wild. That’s where Smithsonian researcher and Panamanian native Gina Della Togna comes in.

Gina Della Togna in the lab. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

Della Togna is working on a number of complex assisted reproduction techniques for Panamanian frog species. She is the first scientist to develop protocols for extracting and freezing sperm from the Panamanian golden frog, a species that is extinct in the wild and a cultural icon in her home country. Scientists could someday use the sperm to infuse populations with additional genetic diversity, key to a species’ overall health.

“When we started, we didn’t know anything about anything,” Della Togna says. “We needed to learn which hormones at what concentrations to use, how to keep the sperm alive long enough to freeze it and the best techniques to freeze it so that the sperm is viable when we thaw it, even years later. It was a challenge, but I love a good challenge.”

Now Della Togna is working on developing similar protocol for other rescue project species, including the mountain harlequin frog, Pirre harlequin frog, variable harlequin frog, limosa harlequin frog and the rusty robber frog. In the future, she plans to get out into the field to capture genetic lineages from frogs in the wild. As she continues to perfect these protocols, Della Togna also aims to collect eggs from female Panamanian golden frogs to use for artificial fertilization with the frozen sperm. And most recently in Panama, she successfully applied a hormone treatment to help six pairs of the limosa harlequin frog and Pirre harlequin frogs breed that hadn’t laid eggs before.

“Breeding frogs is the fundamental step to sustaining captive populations and growing the numbers for release trials,” Gratwicke says. “Gina’s work is of huge applied value to us because we have some very challenging species to breed, and hormone dosing may help us to get them to cycle reproductively, even if we can’t figure out the external reproduction cues.”

For Della Togna, Gratwicke and Becker, the goal is the same: to give these unique species a fighting chance against Bd.

“If these frogs go extinct, nothing can replace them,” Della Togna says. “They are important to the ecosystem and essential to our planet’s equilibrium. There’s no doubt that we’re responsible for getting them back to where they belong.”

From now until the end of August, you can help us #FightForFrogs! Our generous sponsor Golden Frog—a global online services provider with a terrific name—will match donations to the rescue project up to $20,000, helping us raise money critical to our fight for frogs. Your donations during the Fight for Frogs campaign will buy us equipment to care for the frogs in the rescue pods, help us continue to conduct experiments to find a cure, ensure crucial breakthroughs, and ultimately one day see the return of these incredible species to their home in the wild.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a project partnership between the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Houston Zoo, Zoo New England and Smithsonian Institution. You can follow the Fight for Frogs campaign on Twitter using the #FightForFrogs hashtag or on the rescue project’s Facebook page.

Join us as together we Fight for Frogs

Frogs matter. As a kid in nursery school, I remember observing tadpoles metamorphose into froglets right before our eyes in the classroom. It was like watching a magic trick over and over again. As I grew more interested in these cool little creatures, I learned that some frogs reproduce using pouches, others by swallowing their own eggs and regurgitating their young, others still by laying eggs that hatch directly into little froglets. It was like discovering not one magic trick, but an entire magical world—except this world was no illusion, it was real. My formative experiences both in the classroom and out rummaging around cold rainy ponds at night with my best friend and a headlamp spurred me into a career in the biological sciences. They also instilled in me a deep appreciation for the incredible diversity of life.

Frogs matter. As a kid in nursery school, I remember observing tadpoles metamorphose into froglets right before our eyes in the classroom. It was like watching a magic trick over and over again. As I grew more interested in these cool little creatures, I learned that some frogs reproduce using pouches, others by swallowing their own eggs and regurgitating their young, others still by laying eggs that hatch directly into little froglets. It was like discovering not one magic trick, but an entire magical world—except this world was no illusion, it was real. My formative experiences both in the classroom and out rummaging around cold rainy ponds at night with my best friend and a headlamp spurred me into a career in the biological sciences. They also instilled in me a deep appreciation for the incredible diversity of life.

Today I am focused on conserving that incredible diversity specifically among amphibians in Panama, which is home to an astounding 214 amphibian species. Or at least it was. When a deadly amphibian chytrid fungus swept through, nine species disappeared entirely, including the country’s national animal, the beautiful Panamanian golden frog.

Today I am focused on conserving that incredible diversity specifically among amphibians in Panama, which is home to an astounding 214 amphibian species. Or at least it was. When a deadly amphibian chytrid fungus swept through, nine species disappeared entirely, including the country’s national animal, the beautiful Panamanian golden frog.

Since 2009, the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has spearheaded efforts to bring at-risk species into rescue pods to ride out the storm while we work on finding a cure. We’ve worked with partners to conduct several experiments in search of a cure and to better understand why some frogs resist infection and others do not. We have built new facilities that house highly endangered species of amphibians as part of a bigger global push to create an “Amphibian Ark.” These efforts and those of our colleagues around the world give me profound hope for our amphibian friends.

Since 2009, the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has spearheaded efforts to bring at-risk species into rescue pods to ride out the storm while we work on finding a cure. We’ve worked with partners to conduct several experiments in search of a cure and to better understand why some frogs resist infection and others do not. We have built new facilities that house highly endangered species of amphibians as part of a bigger global push to create an “Amphibian Ark.” These efforts and those of our colleagues around the world give me profound hope for our amphibian friends.

But we need your help.

Although frogs are the orchestral backdrop to every pond and forest, frogs have no voice to represent themselves, and they certainly can’t write checks. It’s up to professional conservationists, including the rescue project’s 12 talented conservationists in Panama, to save frogs so that others can enjoy them. This, however, requires money. From now until the end of August, our generous sponsor Golden Frog—a global online services provider with a terrific name—will match donations to the rescue project up to $20,000, helping us raise money critical to our fight for frogs. Your donations during the Fight for Frogs campaign will buy us equipment to care for the frogs in the rescue pods, help us continue to conduct experiments to find a cure, ensure crucial breakthroughs, and ultimately one day see the return of these incredible species to their home in the wild.

Together, let’s make a stand. Together, let’s #FightForFrogs.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a project partnership between the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Houston Zoo, Zoo New England and Smithsonian Institution. You can follow the Fight for Frogs campaign on Twitter using the #FightForFrogs hashtag or on the rescue project’s Facebook page.

Meet Angie Estrada: Amphibian Ambassador

We are a small part of a much larger global effort called the Amphibian Ark program working to coordinate and support global efforts to prevent amphibian extinctions. Learn more about other cool amphibian conservation work at the AArk ambassador’s page and like their Facebook page.

Mission Critical: Amphibian Rescue

This award-winning documentary featuring our race to find a cure for a deadly amphibian disease and to build an amphibian ark in Panama is now available for FREE. Watch the trailer below and download the full feature if you would like to see more on the itunes store for a limited time only.

Rescue Project Successfully Breeds Endangered Frog Species

Limosa harlequin frog (Atelopus limosus) baby on a U.S. quarter. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

The limosa harlequin frog (Atelopus limosus), an endangered species native to Panama, now has a new lease on life. The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is successfully breeding the chevron-patterned form of the species in captivity for the first time. The rescue project is raising nine healthy frogs from one mating pair and hundreds of tadpoles from another pair.

“These frogs represent the last hope for their species,” said Brian Gratwicke, international coordinator for the project and a research biologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, one of six project partners. “This new generation is hugely inspiring to us as we work to conserve and care for this species and others.”

Nearly one-third of the world’s amphibian species are at risk of extinction. The rescue project aims to save priority species of frogs in Panama, one of the world’s last strongholds for amphibian biodiversity. While the global amphibian crisis is the result of habitat loss, climate change and pollution, a fungal disease, chytridiomycosis, is likely responsible for as many as 94 of 120 frog species disappearing since 1980.

Between its facilities at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Gamboa, Panama, and the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center in El Valle, Panama, the rescue project currently cares for 55 adult limosa harlequin frogs of the chevron-patterned form and 10 of the plain-color form. The project has had limited success breeding the plain-color form of this species, and has successfully bred other challenging endangered species, including crowned treefrogs (Anotheca spinosa), horned marsupial frogs (Gastrotheca cornuta) and toad mountain harlequin frogs (A. certus).

Each species requires its own unique husbandry to thrive and breed. The project’s animal care team and scientists learn husbandry techniques as they work with a limited number of individuals. Jorge Guerrel, conservation biologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, arranged rocks in the breeding tank to create the submerged caves that appear to be the preferred egg deposition sites for limosa harlequin frogs. Like other Atelopus species, tadpoles require highly oxygenated, gently flowing water between 22 and 24 degrees Celsius. The tadpoles’ natural food is algal film growing on submerged rocks, which Guerrel and his colleagues re-created by painting petri dishes with a solution of powdered spirulina algae, then allowing it to dry.

The mission of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is to rescue amphibian species that are in extreme danger of extinction throughout Panama. The project’s efforts and expertise are focused on establishing assurance colonies and developing methodologies to reduce the impact of the amphibian chytrid fungus so that one day captive amphibians may be reintroduced to the wild. Current project partners include Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Houston Zoo, Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Zoo New England.

Lindsay Renick Mayer, Smithsonian’s National Zoo

Frog Love on Valentine’s Day

This Valentine’s Day we asked some of the rescue project’s researchers why they love frogs. Here’s what we got back from a few biologists at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. The common link? A life-long love of wildlife.

“My favorite childhood memories revolve around my mother taking me down to the nearest stream and letting me get dirty playing with frogs and salamanders. I loved it so much, I get to do that for a living now! The diversity within all amphibians still amazes me as there is so much we still have to learn. I consider being able to work on projects, which may help save frogs from extinction, to be the absolute coolest part of my job.”

“Since childhood it was snakes, not frogs, that were the focus of hours spent searching woodlands, streams and ponds. Unlike other more noticeable creatures, snakes are decidedly unapparent; unless they happen to be eating a frog! Although, the thrill of finding a snake by following the plaintive screams of a leopard frog never diminished, what increased was my interest in the gradually disappearing prey. So, thanks in part to the appetite of a few alluring garter snakes the equally marvelous world of frogs, toads, salamanders, sirens, and hellbenders opened to me and now inform and enhance days at work and in the field.”

“I fell in love with frogs growing up as a child in Zimbabwe. There was something exhilarating about discovering the translucent, musical jewels that are responsible for the familiar nocturnal soundtrack of my childhood. Unlike any computer games or TV shows, I will carry those first memories of catching frogs around a pond with me for the rest of my life. For me, seeing frogs in the wild stirs emotions of wonder and discovery, and they are accessible to everyone who is willing to take a little extra effort to open their eyes and look.”

–Brian Gratwicke, rescue project international coordinator

Genetic Matchmaking Saves Endangered Frogs

The casque headed tree frog (Hemiphractidae: Hemiphractus fasciatus), is one of 11 species of highest conservation concern now being bred in captivity in Panama. Females carry eggs on their backs where the young complete development hatching out as miniature frogs. DNA barcoding data suggest that populations of H. fasciatus may comprise more than one taxonomic group.

What if Noah got it wrong? What if he paired a male and a female animal thinking they were the same species, and then discovered they were not the same and could not produce offspring? As researchers from the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project race to save frogs from a devastating disease by breeding them in captivity, a genetic test averts mating mix-ups.

At the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, project scientists breed 11 different species of highland frogs threatened by the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which has already decimated amphibian populations worldwide. They hope that someday they will be able to re-release frogs into Panama’s highland streams.

Different frog species may look very similar.

“If we accidentally choose frogs to breed that are not the same species, we may be unsuccessful or unknowingly create hybrid animals that are maladapted to their parents’ native environment,” said Andrew J. Crawford, research associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and professor at Colombia’s Universidad de los Andes. Crawford and his colleagues make use of a genetic technique called DNA barcoding to tell amphibian species apart. By comparing gene sequences in a frog’s skin cells sampled with a cotton swab, they discover how closely the frogs are related.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical nature and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.

—Beth King, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

Photo by Edgardo Griffith.