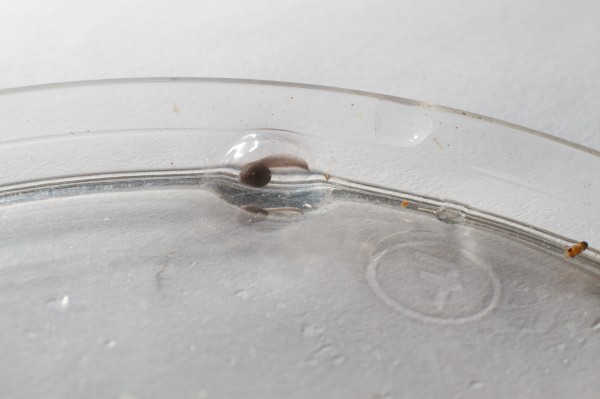

The first captive-bred Andinobates geminisae at the Gamboa Amphibian Research and Conservation Center. Photo by Jorge Guerrel, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) scientists working as part of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project hatched the first Andinobates geminisae froglet born in captivity. The tiny dart frog species only grows to 14 millimeters and was first collected and described last year from a small area in central Panama. Scientists collected two adults to evaluate the potential for maintaining the species in captivity as an insurance population.

“There is a real art to learning about the natural history of an animal and finding the right set of environmental cues to stimulate successful captive breeding,” said Brian Gratwicke, amphibian conservation biologist at SCBI and director of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project. “Not all amphibians are easy to breed in captivity, so when we do breed a species for the first time in captivity it is a real milestone for our project and a cause for celebration.”

Scientists simulated breeding conditions for the adult frogs in a small tank. The frogs laid an egg on a bromeliad leaf, which scientists transferred to a moist petri dish. After 14 days, the tadpole hatched. Scientists believe adult A. geminisae frogs may provide their eggs and tadpoles with parental care, which is not uncommon for dart frogs, but they have not been able to determine if that is the case. In the wild, one of the parents likely transports the tadpole on his or her back to a little pool of water, usually inside a tree or on a bromeliad leaf.

After the tadpole hatched, scientists moved it from the petri dish to a small cup of water, mimicking the small pools available in nature. On a diet of fish food, the tadpole successfully metamorphosed into a froglet after 75 days and is now the size of a mature adult.

Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project scientists are unsure if A. geminisae is susceptible to the amphibian-killing chytrid fungus. However, since it is only found in a small area of Panama and is dependent on primary rain forests, which are under pressure from agricultural conversion, they have identified it as a conservation-priority species.

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project breeds endangered species of frogs in Gamboa, Panama and El Valle, Panama. The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a partnership between the Houston Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, SCBI and STRI. This study was supported by Minera Panama.