Our planet is home to almost 9,000 amphibian species. For more than 100 years, these animals have dramatically suffered the consequences of deforestation, agriculture, wetland drainage, agrochemicals and other pollutants. In recent times, new threats have emerged making 40% of all amphibian species threatened with extinction under “Red List” released by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which was recently updated. New threats include climate change and emerging infectious diseases. Among them, amphibian chytrid fungi causing skin infections play a key role. These fungi have been spread all over the world by humans and induce the disease chytridiomycosis in amphibians, leading to population declines and even extinctions.

Already 30 years ago, researchers, conservationists and other stakeholders have realized the crisis the amphibians are in. Various initiatives, at the global, regional and local scales have been founded to safeguard amphibian diversity including numerous management and action plans. Due to these activities, we massively augmented our knowledge about where declines happen, as well as the mechanisms behind these and how threats interact. This goes hand in hand with enormous engagement for protecting natural habitats and accompanying captive breeding in conservation facilities. Also, diseases and their agents are much better understood. There have been many stories of success and without all the investment, work and passion of dedicated actors many amphibian species would have become extinct by now!

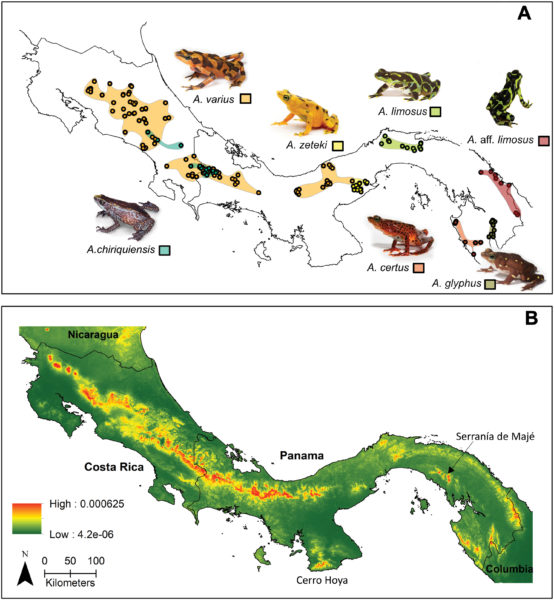

However, it is difficult to appreciate where we stand in overcoming the amphibian crisis. Threats and the vulnerability to them are not equally distributed over all species. Certain amphibians are more susceptible and suffer more. They represent ‘worst-case scenarios’ of the amphibian crisis. For many of them, we lack sufficient information to access their current status. Not so for harlequin toads, genus Atelopus, from Central and South America. These are small, often colourful and day-active animals that inhabit lowland rainforests to high Andean moorlands (páramos) above tree line.

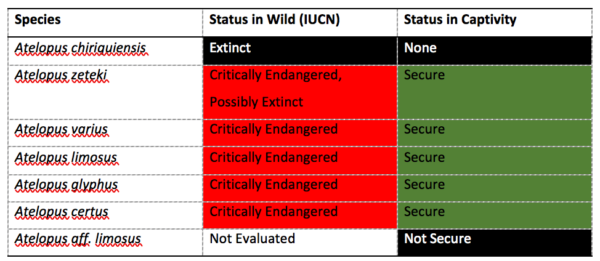

More than 130 Atelopus species are known and – being highly sensitive to threats – many of them have declined and are even feared extinct. Harlequin toads are the poster child of the amphibian crisis, and due to their iconic appearance, scientists have studied population status data since the early 1990s. In a recent study published in Communications Earth and Environment, Lötters and 99 colleagues, mostly conservationists and researchers from countries where harlequin toads naturally occur, compared population status data as of 2004 and of 2022 to examine species-specific trends over the last two decades.

Data from the authors confirm that massive conservation efforts from many scientists, conservationists and local communities have revealed that more than 30 Atelopus species that in part were feared to have vanished are still there! However, evidence suggests that at the same time all species remain threatened and their conservation status has not improved. Factors threatening the remaining harlequin toads remain unchanged and include habitat change and chytrid fungus spread. In addition, the authors demonstrated that in the future harlequin toads suffer from climate change.

Authors conclude that other worst-case amphibians continue to be imperilled demonstrating that the amphibian crisis is still an emergency. Thanks to the tremendous strength put into conservation, by collaborative networks like the recently launched Atelopus Survival Initiative under the umbrella of the Atelopus Task Force of the IUCN Amphibian Specialist Group, these amphibians have not yet vanished. It is now more than ever critical to continue and increase efforts to escape the emergency the amphibian crisis still is.

Lötters, S., A. Plewnia, A. Catenazzi, K. Neam, A.R. Acosta-Galvis, Y. Alarcon Vela, J.P. Allen, J.O. Alfaro Segundo, A. de Lourdes Almendáriz Cabezas, G. Alvarado Barboza, K.R. Alves-Silva, M. Anganoy-Criollo, E. Arbeláez Ortiz, J.D. Arpi L., A. Arteaga, O. Ballestas, D. Barrera Moscoso, J.D. Barros-Castañeda, A. Batista, M.H. Bernal, E. Betancourt, Y.O. da Cunha Bitar, P. Böning, L. Bravo-Valencia, J.F. Cáceres Andrade, D. Cadenas, J.C. Chaparro Auza, G.A. Chaves-Portilla, G. Chávez, L.A. Coloma, C.F. Cortez-Fernandez, E.A. Courtois, J. Culebras, I. De la Riva, V. Diaz, L.C. Elizondo Lara, R. Ernst, S.V. Flechas, T. Foch, A. Fouquet, C.Z. García Méndez, J. E. García-Pérez, D.A. Gómez-Hoyos, S.C. Gomides, J. Guerrel, B. Gratwicke, J.M. Guayasamin, E. Griffith, V. Herrera-Alva, R. Ibáñez, C.I. Idrovo, A. Jiménez Monge, R.F. Jorge, A. Jung, B. Klocke, M. Lampo, E. Lehr, C.H.R. Lewis, E.D. Lindquist, Y.R. López-Perilla, G. Mazepa, G.F. Medina-Rangel, A. Merino Viteri, K. Mulder, M. Pacheco-Suarez, A. Pereira-Muñoz, J.L. Pérez-González, M.A. Pinto Erazo, A.G. Pisso Florez, M. Ponce, V. Poole, A.B. Quezada Riera, A.J. Quiroz, M. Quiroz-Espinoza, A. Ramírez Guerra, J.P. Ramírez, S. Reichle, H. Reizine, M. Rivera-Correa, B. Roca-Rey Ross, A. Rocha-Usuga, M.T. Rodrigues, S. Rojas Montaño, D.C. Rößler, L.A. Rueda Solano, C. Señaris, A. Shepack, F.R. Siavichay Pesántez, A. Sorokin, A. Terán-Valdez, G. Torres-Ccasani, P.C. Tovar-Siso, L.M. Valencia, D.A. Velásquez-Trujillo, M. Veith, P.J. Venegas, J. Villalba-Fuentes, R. von May, J.F. Webster Bernal & E. La Marca (2023): Ongoing harlequin toad declines suggest the amphibian extinction crisis is still an emergency. — Communications Earth and Environment, 4, 412. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-023-01069-w