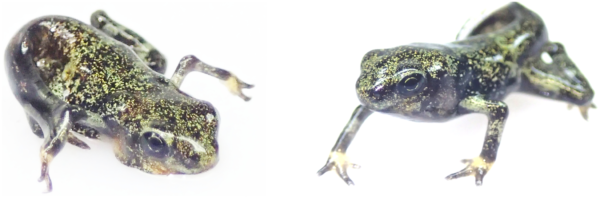

Rearing frogs in captivity has its own unique challenges, one problem that has been a persistent issue in the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is spindly leg syndrome (SLS). This common musculoskeletal disease is mostly associated with captive amphibian breeding. SLS is a condition where legs of newly metamorphed amphibians, with otherwise healthy and typical development, are poorly developed and cannot support the weight or newly metamorphed froglets. Ultimately, SLS leads to death as the animal is unable to move or feed themselves. A brief review online will reveal a host of theories and potential remedies for the condition ranging from parental nutrition to water quality and dietary supplements, but there are very few replicated peer-reviewed experiments identifying the cause of this disease.

As an intern with the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project I teamed up with Orlando Garcés a graduate of the University of Panama and employee of the project to conduct an experiment primarily funded by the Morris Animal Foundation. We had observed that SLS was most prevalent in water that did not have any supplementary calcium and we knew that incoming water to our facility was very soft (lacking in calcium hardness). Bone growth is the symptom of SLS, therefore, we decided to look at the principle minerals affecting bone growth: calcium and phosphate. Tadpoles can gain calcium through their diet but they absorb about 70% of their calcium from the water through their gills and skin. The collected calcium is then stored in endolymphatic sacs in their heads and used during metamorphosis when tadpoles’ skeleton turns from cartilage into bone and limbs begin to grow.

We took 600 Atelopus varius tadpoles and divided them into three calcium treatments (low, medium, high) and then divided those into two groups one with added phosphate and one without added phosphate. We monitored our tadpoles until they metamorphosed, at which point we looked at their legs and body posture to determine whether or not they had SLS. We found that calcium supplementation drastically increased survivorship overall and that the medium and high calcium groups had less SLS than the low calcium groups. Addition of phosphate also decreased the prevalence of SLS in low calcium treatment.

Based on the results of this study we were able to determine that SLS in harlequin frogs, is linked to an imbalance in calcium and phosphate homeostasis. Therefore, our current husbandry recommendation to reduce SLS in frogs and toads is to consider checking water hardness to determine if it is too soft. We also advise against over feeding tadpoles which has been shown to cause an increase in SLS prevalence in another experiment. We hope that our findings can guide future SLS research and help to lower the prevalence of SLS in captive amphibians, improving animal welfare. This research will help to improve the long-term sustainability of captive populations while researching solutions for the amphibian chytrid fungus and eventual reintroduction of these frogs back into the wild.

Lassiter, E., Garcés, O., Higgins, K., Baitchman, E., Evans, M., Guerrel, J., Klaphake, E., Snellgrove, D., Ibáñez, R. and Gratwicke, B., 2020. Spindly leg syndrome in Atelopus varius is linked to environmental calcium and phosphate availability. PloS one, 15(6), p.e0235285.

By Elliot Lassiter and Orlando Garcés