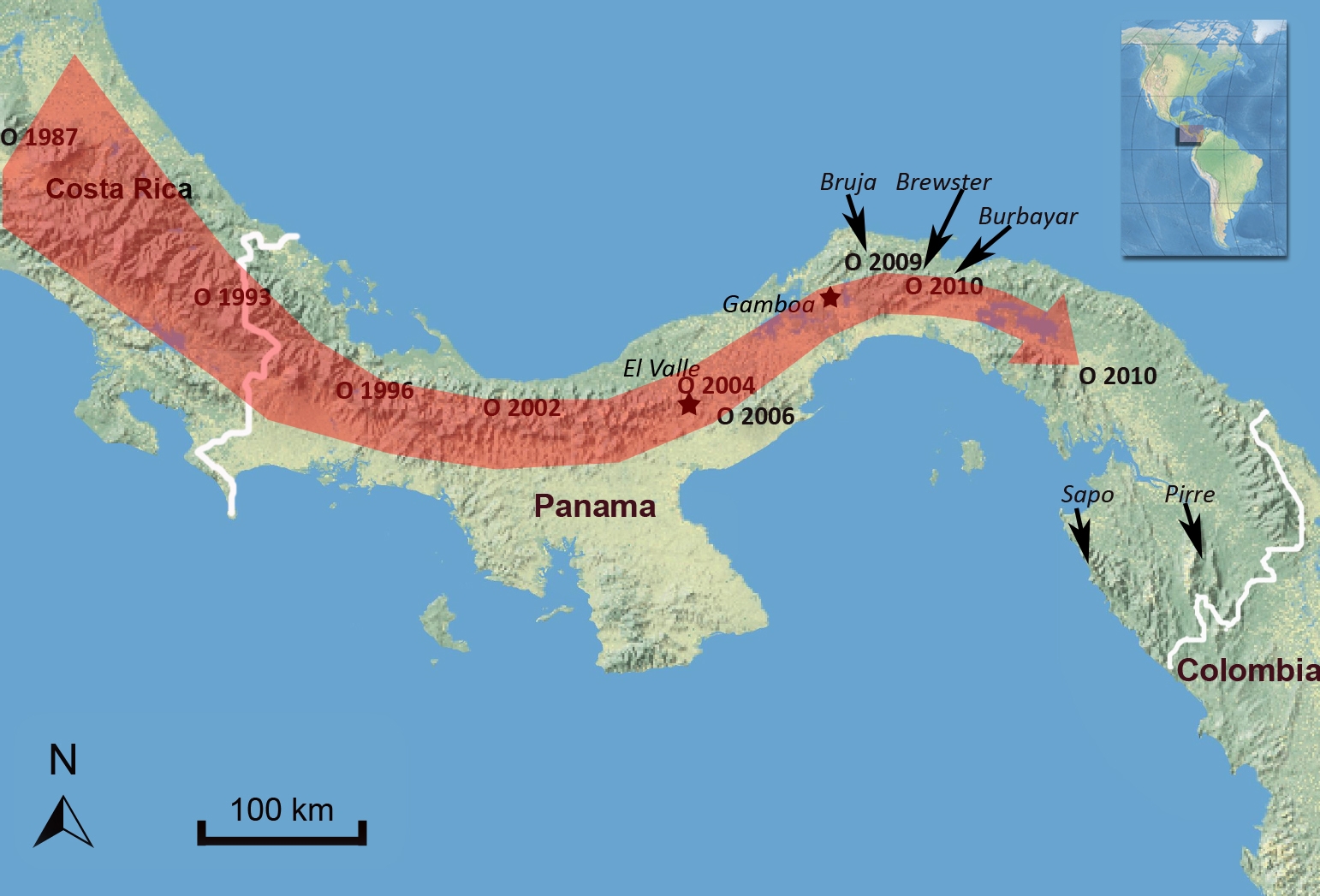

Enigmatic Fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) declines in the Netherlands have been attributed to the recently described fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bs). Since 2010, the S. salamandra population at Bunderbos, Netherlands has decreased by 96%. An Martel et al’s recent Science paper showed that some US salamander species are highly susceptible to Bs, confirmed its occurrence in the pet trade, and noted that it has not yet been detected in the US. Large numbers of live salamanders are legally imported into the US each year for the pet trade. In the first 6 months of 2014, for example, 3,445 fire salamanders imported into the US, mostly from Slovenia.

Enigmatic Fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) declines in the Netherlands have been attributed to the recently described fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bs). Since 2010, the S. salamandra population at Bunderbos, Netherlands has decreased by 96%. An Martel et al’s recent Science paper showed that some US salamander species are highly susceptible to Bs, confirmed its occurrence in the pet trade, and noted that it has not yet been detected in the US. Large numbers of live salamanders are legally imported into the US each year for the pet trade. In the first 6 months of 2014, for example, 3,445 fire salamanders imported into the US, mostly from Slovenia.

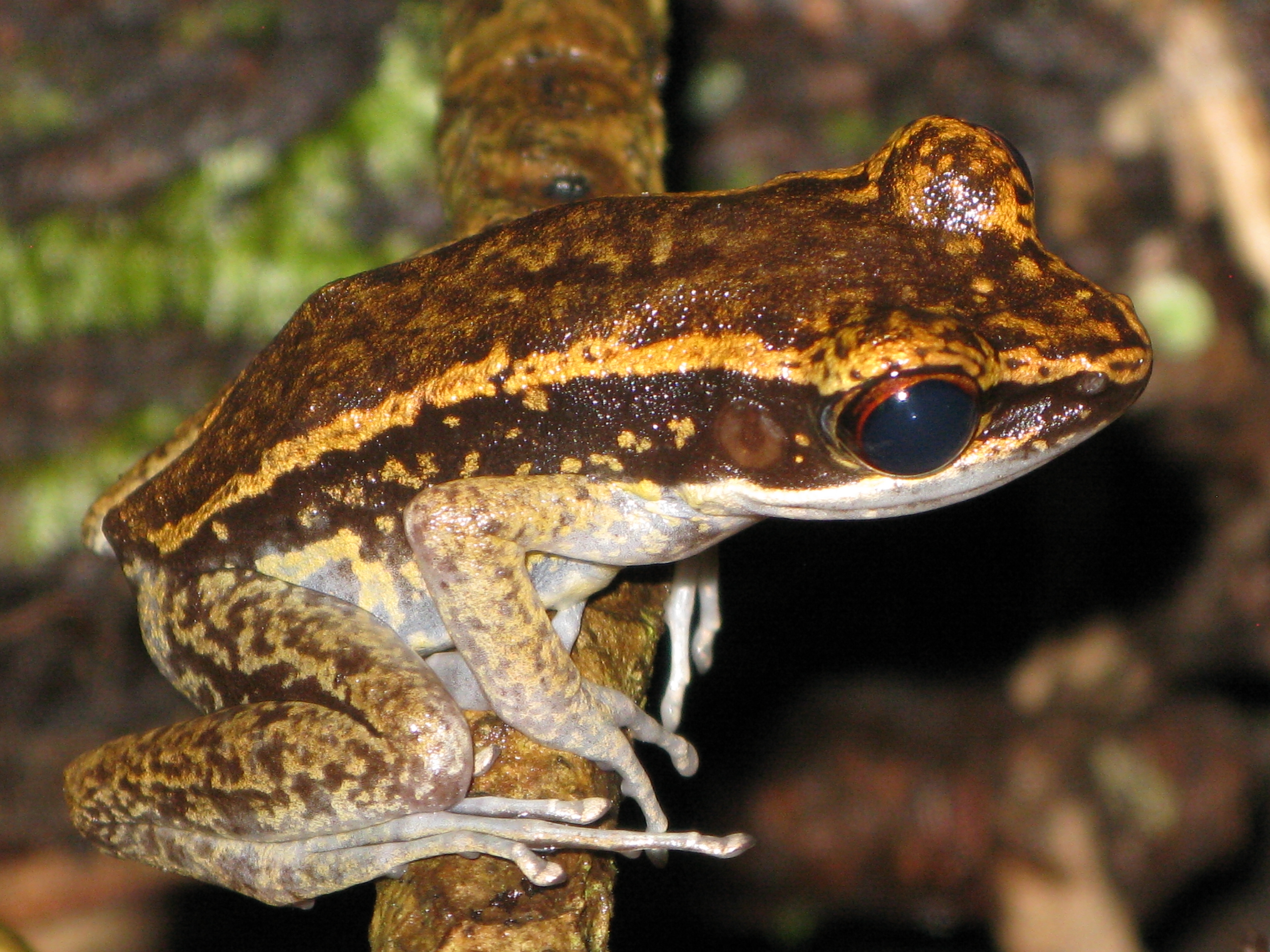

The genus Batrachochytrium, which before the discovery of Bs solely included Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), has gained an infamous reputation for global amphibian declines. Biologists believe that we are witnessing the sixth mass extinction in part because of the virulence and global spread of Bd among the world’s amphibians. The discovery of this new pathogen and our improved understanding of the ravaging effects of emerging wildlife disease raise concerns that US salamanders could share the same fate.

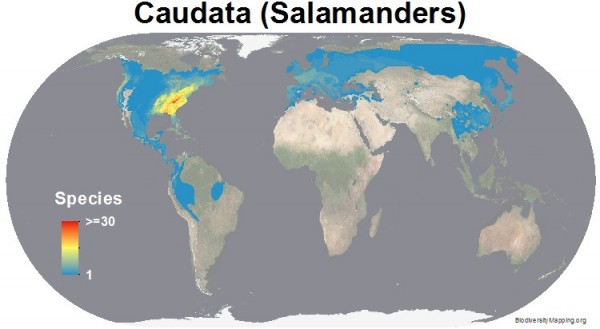

The US is a biodiversity hotspot for salamanders

Appalachia is a global salamander biodiversity hotspot (Source: http://www.biodiversitymapping.org/amphibians.htm)

The Appalachian Mountains are a renowned biodiversity hotspot for salamanders. The potential threat of this emerging pathogen in the US is therefore magnified, and it is imperative that we keep this disease out of the US. Salamander genetic diversity in the Appalachians is the highest in the world with 72 salamander species that are mostly endemic. The United States is home to nine out of ten salamander families and four of the ten extant salamander families are endemic to the United States including amphiumas, Pacific giant salamanders, torrent salamanders and sirens. Mole salamanders are also found in Canada and Mexico, but nearly all of their biodiversity is contained with U.S. borders. Giant salamanders are a primitive lineage of giant salamanders with three extant species, located in the U.S., Japan, and China. The hellbender is one of the giants and has found refuge in the Appalachian Mountains since amphibians originated, some 360 million years ago.

The ecological role of salamanders, the smaller majority, can often go unnoticed, but consider this biomass assessment of salamanders in Appalachia. One classic mark-recapture study in the eastern US noted “The biomass of salamanders is about twice that of birds during the bird’s peak breeding season and is about equal to the biomass of small mammals” (Burton and Likens 1975). With densities this high, a novel salamander-specific pathogen to which these animals have never been exposed have the potential be able to spread like wildfire, much like Bd spread through naïve Neotropical amphibian populations.

Immediate action is needed

We should immediately halt the importation of salamanders from any overseas sources, unless they can be certified free from Bs and Bd. In May 2008 the OIE, which is the organization created to mitigate zoonotic diseases (i.e., anthrax, mad cow disease, etc.), recognized Bd as a notifiable disease. Stricter trade regulations recommended by OIE would substantially reduce the spread of both Bs and Bd, however the OIE changes have not been adopted by the US Department of Agriculture and Interior and until doing so there are no legal means to reject infected shipments. A joint statement from the Amphibian Specialist Group and Amphibian Survival Alliance calls for immediate policy actions to stop the further spread of devastating wildlife diseases, and this time it is not too late to do something about it.

by Blake Klocke