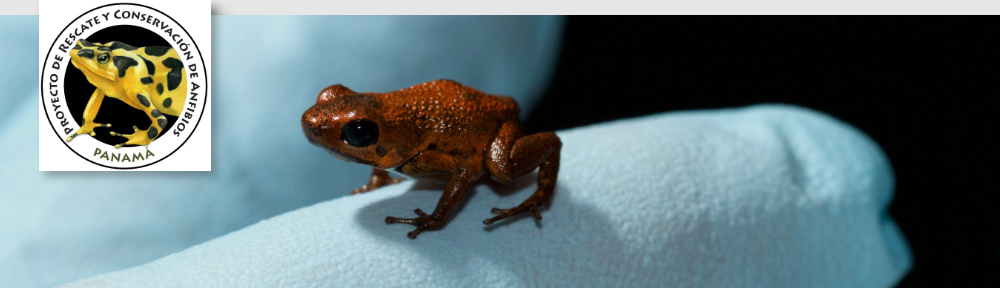

This little hourglass tree frog (Dendropsophus ebrecattus) was among my favorites that we caught in the rainforest.

One full week of being nothing but frog mad. When I close my eyes, it’s frogs that I see. When there’s a nearby chirp, it’s frogs that I hear. And when I think about conservation, it’s frogs that I feel. One full week clearly isn’t enough.

It’s enough, though, to give me a real sense of what, exactly, we are working so hard to conserve–the biodiversity, the beauty, the values and the hope. It isn’t a matter of “should” or “should not.” It’s a matter of “must.” That’s exactly what I told the guy at customs checking my passport upon my return to the States yesterday when he asked what I was doing in Panama. I’m sure he didn’t expect a lecture about why it’s important for us to save frogs–or for me to write down the website of this project–but I hope that he got the message.

I left Panama yesterday with an even stronger conviction, if that’s possible. I am relieved that there are those among us who are dedicated to biodiversity and to preserving what this beautiful planet has to offer. Those who understand the difference between using and abusing power. Amphibians have strong advocates and I will continue to help seek new recruits.

With that, I offer a few of my favorite frog memories from the week and am hopeful that others will be able to see these treasures in their natural habitats for years to come.

10. Frog talk. Every day I looked forward to lunchtime at Summit Zoo with the keepers; the project’s international coordinator, Brian Gratwicke; and project volunteer, Jeff Coulter. Although we didn’t all speak the same language, our shared passion carried us through.

9. Frog pit stops. No matter where we were driving to or from at night, Brian would roll his windows down to listen to the frogs. “We’re just going to make a quick pit stop. Is that okay?” he’d ask, even as Jeff and I were already jumping out of the car. Many grand excursions came out of these frog pit spots.

8. The frog whisperer. When Jeff interacted with the frogs in the wild, the animals that would leap out of my hands posed very nicely for photos in his. It was delightful to watch the delicate way he held the animals.

The rescue project's international coordinator, Brian Gratwicke, shows some love for the cane toad (Bufo marinus).

7. Frog lovers’ heaven. One of the trip’s highlights was wandering around El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, peering into one tank and then another, excited each time to discover whichever species was housed there. I had only ever read about most of the species in captivity there.

6. Amplexus. One day after the keepers put a pair of Toad Mountain harlequin frogs (Atelopus certus) together in a beautiful breeding tank, we found the two animals in amplexus, moving the project ahead more quickly than expected.

5. Frog calls. Brian, Jeff and I spent many nights out in the rainforest collecting frogs for photo shoots the next morning. On one particularly successful night, one little frog decided to call late at night from our porch, keeping Brian awake and giggling (which, in turn, kept me awake and giggling).

4. Leaf litter toad mystery. One evening on a night quest we were stumped when we were suddenly surrounded by the calls of dozens, if not hundreds, of frogs. I recorded the call and played it back to get them going again so we could locate them. After about 30 minutes of looking in the trees and finding nothing, I found a leaf litter toad (Bufo typhonius alatus) on the ground. Turns out this very common species had tricked us into thinking they were in the trees.

3. Frog queen. That’s how I think about the female harlequin frog (Atelopus limosus) of the highland variation that may be the very last of her kind. Every day that I was at Summit, I made sure to check in on her. If the everyone was as gentle with and respectful of the natural world as the keepers were with her and all of the other frogs in the ark, the rescue project would never be necessary.

2. Smokey jungle frog. A frogging trip to Barro Colorado Island quickly turned stinky after I nabbed a very large smokey jungle frog. Unbeknownst to me, a primary mode of defense for smokey jungle frogs is to squawk loudly, rather like a chicken, and to emit a mucus that smells foul. I only discovered this as it unfolded, resulting in both a squawking frog and a squealing/swearing/panicked Lindsay.

1. Sierra Llorona frogs. One day we ventured to Sierra Llorona, which is the origin of the lowland variation of the harlequin frogs (Atelopus limosus) that we have in captivity at Summit. To see these animals in the wild was thrilling–and to top that, the first frog that I caught was a female (an unusual find). We swabbed about 10 frogs to test for chytrid, but that female was my favorite. I set her free with the wish that she is chytrid free and ready to reproduce and that that will be the future for these animals–and the reality someday for all others we have in captivity.

—Lindsay Renick Mayer, Smithsonian’s National Zoo