The five keepers for the rescue project at Summit Zoo (left to right): Nancy Fairchild, Rousmary Betancourt, Angie Estrada, Jorge Guerrel, Lanky Cheucarama.

Our next door neighbors are: a margay cat named Derek, a couple of Geoffroy’s tamarins and an ocelot. Across the street lives a troop of white face capuchins and every day we pass the parrots as they try to hit on us and say “hola,” no matter how many times we ignore them.

We are the keepers at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project at the Summit Municipal Park in Panama.

We take care of 191 frogs, from seven species, all of them native to Panama. Though each one of us has our own favorite frog—Kuno, Danielito, Chasky, James Bond and Survivor, for example—we make sure they all have everything they need to be happy and safe in their home at the zoo.

Our frogs need a lot of attention! We have to keep them healthy, clean and fed. Maybe it doesn’t sound like that big of a deal, but each of those tasks takes a tremendous team effort, a high level of responsibility, tons of time and even a bit of intuition.

To ensure healthy frogs, first we treat the animals for chytridiomicosis (a skin disease caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd) once they get back from rescue missions in the mountains of eastern Panama. Chytridiomicosis is a fungal skin disease that’s been killing amphibians in the wild for more than two decades and that is spreading fast. Treatment days are awful! We often get nervous and anxious because we know that for some of the frogs it’ll be too late, but we’re relieved at the same time when the majority of them survive. After they are treated, the new frogs are ready to be part of our collection. The hard part really comes after treatment.

A chytrid-free frog does not automatically mean a healthy frog. Before and after they become part of our collection, the frogs can be underweight or have parasites. It is part of our job to hand feed them if necessary and sometimes to remove very active worms under their skin. We need to make sure the frogs take their medicine on time, with the correct dose and with proper follow-up. None of this would be possible without the help and supervision of a group of vets and keepers from other conservation centers and zoos who trained us and are patient enough to receive a lot of emails and phone calls from us.

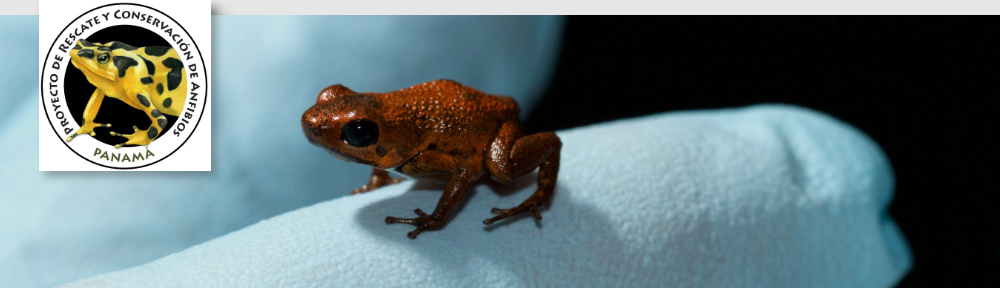

One of the many frogs that keepers for the rescue project care for at Summit Zoo. (This is la loma tree frog, or Hyloscirtus colymba)

Frogs don’t need to take a bath to stay clean, though their environment needs to be cleaned regularly. Amphibians are very sensitive to changes in their habitat because of their permeable skin and the fact that during metamorphosis, they spend part of their life stages in both ecosystems: aquatic and terrestrial. These are some of the reasons why they are declining so rapidly in the wild. When permeable skin comes in contact with contaminated water or soil, frogs can get infected by Bd. In our control environment in the pod, we need to clean the frogs’ enclosures, especially the ones in quarantine. We change and clean all the tanks twice a week, change and clean their plants and leaves, spray water on the tanks that don’t have misting systems and remove the feces.

Last but not least: frogs need to eat! What do our frogs eat? We would need many blog posts to fully explain how we manage to keep alive a room full of two species of fruit flies, springtails and earthworms; and an even larger room with 95 plastic boxes full of crickets and a couple containers of superworms. The latest additions to the menu are a working colony of cockroaches and a brand new outdoors house for grasshoppers. You can say that these frogs are well fed…maybe too well. They eat so much that we’re even putting a few of them on a diet this week!

Did we mention that all of this is not enough to save the species? To do that, we need to breed them too. Reproduction is a very different story. We basically need to create the perfect scenario so the frogs can get in the mood. And getting them in the mood can take from two days (such as for the Toad Mountain harlequin frog, or Atelopus certus) or eight months (as is the case for La Loma leaf frogs, or Hyloscirtus colymba).

This is part of our daily work; we love it and we are very proud of it. Though some people call us “frog heroes,” we are proud to be part of a group of scientists, keepers, vets, volunteers and frog lovers who are trying to safe these beautiful and interesting animals all over the world.

–Angie Estrada, Nancy Fairchild, Rousmary Bethancourt, Jorge Guerrel, Lanky Cheucarama, keepers for the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project at the Summit Zoo in Panama.