A recent rule put in place in 2016, restricting the international import of 201 salamander species into the United States, aimed to prevent the newly discovered deadly salamander fungal disease, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal), from entering the country. In a new study published Oct. 13 in Scientific Reports, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists reveal that the moratorium seemingly has a chance to do its job effectively.

Researchers swabbing an emperor newt at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. Emperor newts belong to a genus of newts from Asia that are currently subjected to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s moratorium on salamander imports because of the risk that they may carry the deadly salamander fungal disease, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal).

“When the moratorium went into effect, we did not know if Bsal was already in the United States in pet salamanders and whether we were closing the barn door after the horse had already escaped,” said Brian Gratwicke, SCBI amphibian conservation biologist and paper senior author. “Our study did not find the pathogen in pet salamander populations in the United States, which is good news for native salamanders, especially in the Appalachian region—a salamander biodiversity hotspot. It also means that we must continue to be vigilant and prevent the disease from entering the country.”

The study marks the first general survey for Bsal in pet salamanders in the United States. The researchers worked with the Amphibian Survival Alliance to mail out sampling kits to salamander pet owners. In return, the team received skin swab samples from 639 salamanders belonging to 65 species, many of which are potential carriers of Bsal. None of the samples came back with evidence of Bsal, according to tests conducted in SCBI’s Center for Conservation Genomics.

“Working with the pet-hobbyist community on this project gave us a chance to alert this key group to a potential problem and was critical in determining whether Bsal has been imported into the United States,” said Blake Klocke, George Mason University’s Department of Environmental Science and Policy doctoral student, researching with SCBI and lead author on the study. “We hope that they will continue to be watchdogs for signs of Bsal and will implement testing and biosecurity protocols into their regular routine to prevent the possible spread of disease in the future.”

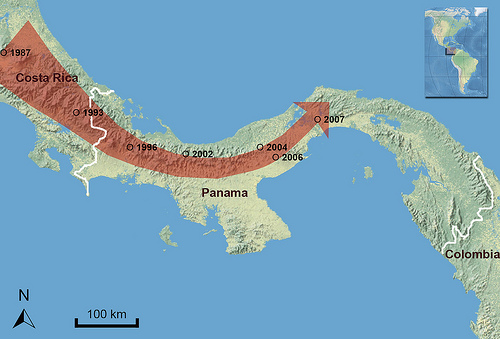

Bsal was discovered after populations of fire salamanders in the Netherlands experienced catastrophic declines from the disease, which was likely introduced from Asia, the source of most international exports of salamander species for the pet trade. Bsal is similar to a frog-killing fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which has been a major driver of global amphibian declines and extinctions. Bsal has been detected in the wild in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and Vietnam, as well as in in captive individuals in the United Kingdom and Germany.

The Lacey Act, which includes the 201 species of salamanders the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service list as “injurious wildlife” (those most susceptible to Bsal or likely to spread Bsal) limits both the import of these animals from other countries and their transfer over state lines. According to the paper, the Lacey Act decision reduced the number of salamanders imported to the United States from 2015 to 2016 by 98.4 percent.

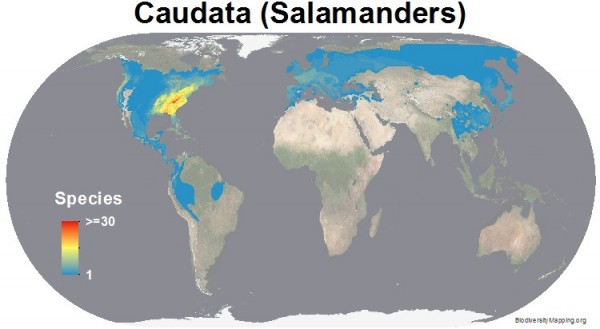

The United States is home to 190 native species of salamanders. The Scientific Reports study complements SCBI’s ongoing tests of salamanders in the wild, which have also come back negative for Bsal. SCBI will continue to screen for the disease in the wild and work with collaborators on developing methods to manage the spread of Bsal should it be introduced into the wild.

“Salamanders play a key role in maintaining the health of our forests and may even help regulate climate,” said Carly Muletz-Wolz, SCBI research scientist and paper co-author. “If Bsal were to hitch a ride to the eastern United States specifically, where salamanders are particularly abundant, it could spread quickly and result in catastrophic changes to the ecosystems. It is imperative that we do all we can to prevent the introduction of Bsal into the country and that we continue to monitor our wild populations so we can take swift action if needed.”

The paper’s additional authors are Matthew Becker and Robert Fleischer, SCBI; James Lewis, Rainforest Trust; and Larry Rockwood and A. Alonso Aguirre, George Mason University.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-13500-2