When researchers discovered Craugastor evanesco in the rainforests of Panama, they called it the vanishing robber frog to signify just how quickly the deadly infectious amphibian disease chytridiomycosis had devastated its population. By the time the researchers had published about the new species in 2010, the vanishing robber frog had already disappeared from the park where they had discovered it.

Now, however, the vanishing robber frog may have a fighting chance at a future thanks to the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, which in December became the first program to breed the species in human care. After multiple attempts at breeding the species since 2015, a single pair has now produced one offspring—a success that has encouraged a cautious optimism that the rescue project can replicate the effort.

“A single individual doesn’t make a successful captive breeding program, but demonstrates that it can be done,” says Brian Gratwicke, an amphibian conservation biologist for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and rescue project international coordinator. “Every journey begins with the first step and this is a critical first step, not just for this species, but potentially for other endangered amphibians with similar reproductive needs.”

The rescue project, a world-class amphibian center run by SCBI and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, currently has a founding population of 20 males and 20 females of the vanishing robber frog. Conservationists collected the frogs from a lowland site in central Panama where the rescue project is working with the support of Minera Panama S.A. to conserve amphibians in the area. But bringing a new and critically endangered species into human care requires learning its own unique husbandry and reproductive needs before it blinks out of existence—sometimes resulting in insurmountable challenges.

“Piecing together a species’ natural history with artificial systems, we can recreate to the best of our abilities an environment where the animals feel comfortable enough to breed,” said Heidi Ross, STRI’s director of El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, whose expertise and persistence led to the successful first-time breeding of the species. “If we can get them to this point, to become sexually active in our artificial habitat, then we can simply tweak the system based on what worked, what did not work, and what materials are at our disposal. What we arduously do day in and day out is make sure we are providing the basic needs to the animals so that they help us help them from going extinct in the wild.”

The Craugastor group of frogs has a unique reproductive system called direct development—they bury eggs in wet sand and fully formed miniature adults hatch from the eggs. Understanding the frogs’ reproductive cues, special dietary needs and how to emulate the natural environment is essential to successful breeding, Ross says.

“Given the current difficult situation for amphibians in our region, this project represents scientific and biological hope, not only for this species of frog, but also for the recovery of Craugastor evanesco within its distribution range,” said Blanca Araúz, biologist and biodiversity superintendent of Minera Panamá. “As one of the species of interest for our project Cobre Panamá, its reproduction in captivity is important. Because the deadly infectious disease acts fast, experienced scientists can control the infection in these frogs and breed them under better conditions.”

Although scientists are still occasionally finding individual vanishing robber frogs in the field, they have not found a viable, self-sustaining population. Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines of amphibian species worldwide. This particular group of frogs in the Craugastor rugulosus series are particularly susceptible to chytridiomycosis with three closely related species in Panama having disappeared, putting extra pressure on ensuring the survival of Craugastor evanesco.

Although scientists are still occasionally finding individual vanishing robber frogs in the field, they have not found a viable, self-sustaining population. Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines of amphibian species worldwide. This particular group of frogs in the Craugastor rugulosus series are particularly susceptible to chytridiomycosis with three closely related species in Panama having disappeared, putting extra pressure on ensuring the survival of Craugastor evanesco.

“It’s all a learning curve,” Gratwicke says. “I’m hopeful that we’ll be able to replicate this breeding event to develop a sustainable breeding program. If we can do that, we’ll be able to get this species back out in the wild as soon as we figure out how to safely do so. If we can do that, it’ll be time to celebrate.”

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is a partnership between the Houston Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, SCBI and STRI.

Frogs matter. As a kid in nursery school, I remember observing tadpoles metamorphose into froglets right before our eyes in the classroom. It was like watching a magic trick over and over again. As I grew more interested in these cool little creatures, I learned that some frogs reproduce using pouches, others by swallowing their own eggs and regurgitating their young, others still by laying eggs that hatch directly into little froglets. It was like discovering not one magic trick, but an entire magical world—except this world was no illusion, it was real. My formative experiences both in the classroom and out rummaging around cold rainy ponds at night with my best friend and a headlamp spurred me into a career in the biological sciences. They also instilled in me a deep appreciation for the incredible diversity of life.

Frogs matter. As a kid in nursery school, I remember observing tadpoles metamorphose into froglets right before our eyes in the classroom. It was like watching a magic trick over and over again. As I grew more interested in these cool little creatures, I learned that some frogs reproduce using pouches, others by swallowing their own eggs and regurgitating their young, others still by laying eggs that hatch directly into little froglets. It was like discovering not one magic trick, but an entire magical world—except this world was no illusion, it was real. My formative experiences both in the classroom and out rummaging around cold rainy ponds at night with my best friend and a headlamp spurred me into a career in the biological sciences. They also instilled in me a deep appreciation for the incredible diversity of life. Today I am focused on conserving that incredible diversity specifically among amphibians in Panama, which is home to an astounding 214 amphibian species. Or at least it was. When a deadly amphibian chytrid fungus swept through, nine species disappeared entirely, including the country’s national animal, the beautiful Panamanian golden frog.

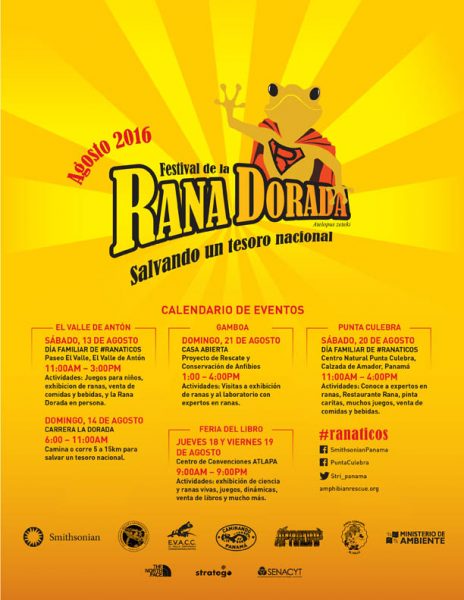

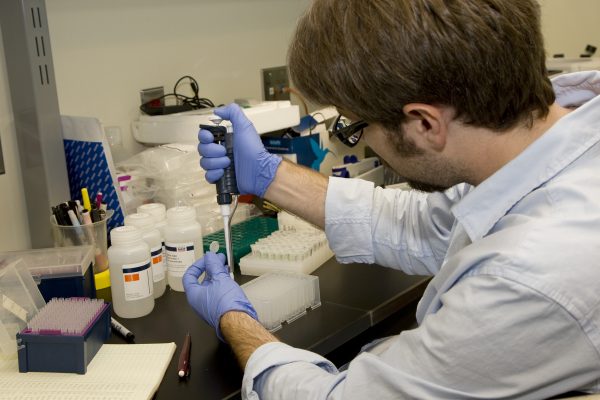

Today I am focused on conserving that incredible diversity specifically among amphibians in Panama, which is home to an astounding 214 amphibian species. Or at least it was. When a deadly amphibian chytrid fungus swept through, nine species disappeared entirely, including the country’s national animal, the beautiful Panamanian golden frog. Since 2009, the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has spearheaded efforts to bring at-risk species into rescue pods to ride out the storm while we work on finding a cure. We’ve worked with partners to conduct several experiments in search of a cure and to better understand why some frogs resist infection and others do not. We have built new facilities that house highly endangered species of amphibians as part of a bigger global push to create an “Amphibian Ark.” These efforts and those of our colleagues around the world give me profound hope for our amphibian friends.

Since 2009, the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has spearheaded efforts to bring at-risk species into rescue pods to ride out the storm while we work on finding a cure. We’ve worked with partners to conduct several experiments in search of a cure and to better understand why some frogs resist infection and others do not. We have built new facilities that house highly endangered species of amphibians as part of a bigger global push to create an “Amphibian Ark.” These efforts and those of our colleagues around the world give me profound hope for our amphibian friends.