Datos remarcables

Participantes: 6280

Voluntarios: 44

Grupos escolares: 34 (aproximadamente 1000 niños)

Eventos: 9

Panfletos distribuidos: 1450

Galletas de rana comidas: 100

Cobertura mediática

Radio/Anuncios TV: 5

Artículos en prensa: 4

Apariciones en la web: 4

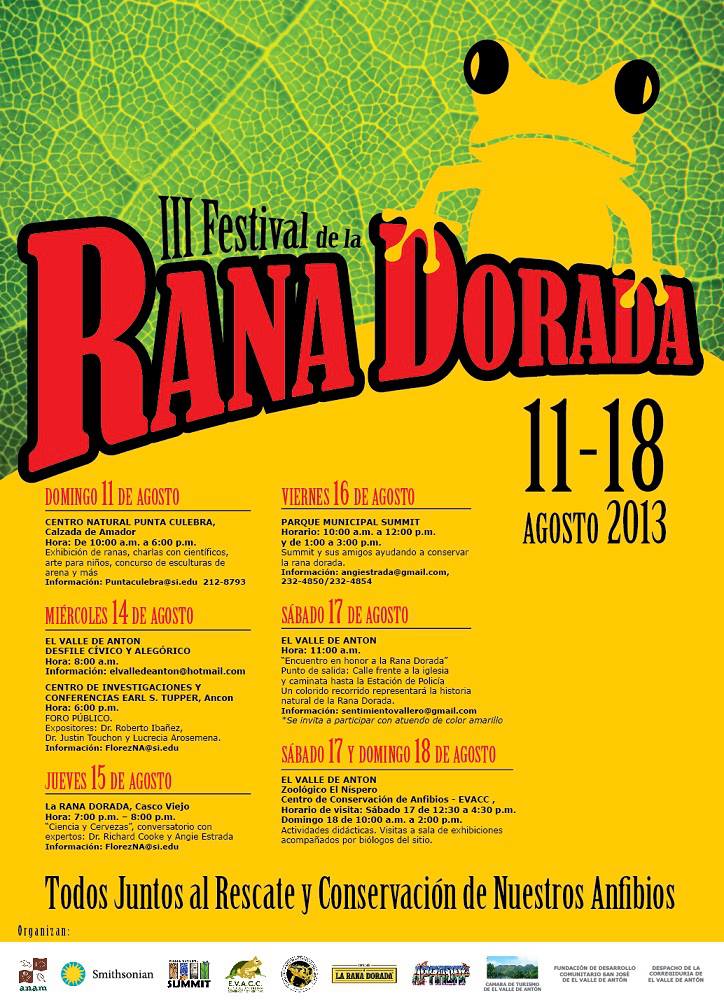

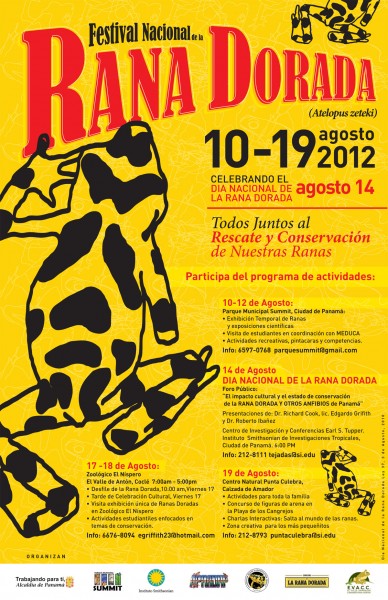

El tercer festival anual de la rana dorada, con distintos eventos a lo largo de Panamá, unió a locales y visitantes de todo el mundo en una sola misión; celebrar y conservar uno de los tesoros de Panamá, los anfibios.

El festival dio comienzo el domingo 11 de agosto en el Centro de Naturaleza Punta Culebra del Smithsonian, donde los miembros del Centro de Rescate de Anfibios de Gamboa debatieron e hicieron demostraciones para los visitantes de todas las edades. Los niños compitieron para hacer la mejor escultura con forma de rana en la playa del centro y a continuación decoraron sus propias máscaras de rana dorada. Los visitantes aprendieron sobre la crisis que acecha a la población de anfibios de la región (desde el mortal hongo Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), hasta la destrucción de su hábitat) y las diferentes maneras de ayudar a preservar estas especies de anfibios de gran valor. Fue un día lleno de diversión para todas las edades.

Escultura de arena de una rana en Punta Culebra. Foto: Instituto de investigación tropical del Smithsonian.

El instituto de investigación tropical del Smithsonian (STRI por sus siglas en ingles) albergó varios eventos durante la semana tanto en inglés como en castellano. En las conferencias semanales «Tupper Talk» del STRI la Dr. Myra Hughey habló sobre su innovadora investigación de cómo el entender los componentes bacterianos de la piel de las ranas puede ayudar a dilucidar formas de combatir la infección Bd. La conferencia de Hughey fue dirigida al ámbito científico, no obstante, al día siguiente tuvo lugar un foro público que ofreció a los visitantes de todas las edades, expertos o no, la oportunidad de escuchar a varios investigadores de renombre. Como el Dr. Roberto Ibanez, uno de los principales científicos del Proyecto de Rescate y Conservación de Anfibios de Panamá (PARC por sus siglas en inglés), también tomó parte Lucrecia Arosemena, cuya incansable labor ayudó a que la legislación panameña reconociera el 14 de agosto de 2010 el primer día nacional de la rana dorada. La nota humorística vino de manos del Dr. Justin Touchon, que nos descubrió interesantes y poco conocidos datos sobre las ranas. Por ejemplo, antes de su conferencia no tenía ni idea de que algunas ranas hembra seleccionan a su pareja basándose en la complejidad de sus cantos, o que estos cantos que también son capaces de realizar las hembras, hacen a las ranas más vulnerables a los predadores como los murciélagos.

En un continuado intento por involucrar al público, el personal del STRI y del PARC dio otra conferencia en el bar La Rana Dorada en el Casco viejo, donde el Dr. Richard Cooke cautivó a muchos viandantes con sus fábulas sobre las propiedades psicotrópicas de las ranas, y con la conferencia titulada «No es fácil ser verde». Por último, Angie Estrada hizo un llamamiento por la conservación y la acción. Las conferencias fueron tan inspiradoras que al final de ese mismo día muchos de los espectadores decidieron ser voluntarios del PARC.

La semana terminó con eventos para escolares y familias en el Zoo de la Cima de Gamboa y en el Centro de Conservación de anfibios de El Valle. A lo largo del fin de semana, los visitantes pudieron ver las ranas (incluyendo ranas doradas nacidas en cautividad), aprender sobre las valiosas contribuciones que los anfibios hacen a los ecosistemas panameños y descubrir cómo ayudar a conservar estos animales. En El Valle, el desfile local de la rana dorada contó con varias carrozas y distintos trajes, como una niña vestida de princesa rana dorada u otra de renacuajo con una gran exactitud morfológica. Tras haber aprendido que las ranas doradas se comunican mediante un lenguaje corporal, algunos niños elaboraron una danza imitando estos movimientos. Cuando el atardecer caía por las montañas, escuché a una adolescente explicarle a otra: «Si yo fuera una rana dorada así es como llamaría a mi compañero». Sus manos rodearon su torso y después levantó sus palmas al cielo. Desde la distancia probablemente parecía otra adolescente mas saltando al ritmo de su canción favorita, pero yo estaba lo bastante cerca para escucharla explicar: «Y así es como protegería mi territorio». Supe entonces, que este baile no surgía de la energía sobrante de una adolescente en vacaciones, sino del compromiso que después lleva a la acción.

-Elizabeth Wade, Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project Volunteer

Traducio por -Maria Ballesteros Rivas