A New Review of Chemicals Produced by the Toad Family, Bufonidae

As human diseases become alarmingly antibiotic resistant, identification of new pharmaceuticals is critical. The cane toad and other members of the Bufonidae family produce substances widely used in traditional folk medicine, but endangered family members, like Panama’s golden frog, Atelopus zeteki, may disappear before revealing their secrets. Smithsonian scientists and colleagues catalog the known chemicals produced by this amphibian family in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology highlighting this largely-unexplored potential for discovery.

“We’re slowly learning to breed members of this amphibian family decimated by the chytrid fungal disease,” said Roberto Ibañez, Panamanian staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and in-country director of the Panama Amphibian Conservation and Rescue (PARC) project. “That’s buying us time to understand what kind of chemicals they produce, but it’s likely that animals in their natural habitats produce an even wider range of compounds.”

15 of 47 frog and toad species used in traditional medicine belong to the family Bufonidae. For millennia, secretions from their skin and from glands near their ears called parotid glands, as well as from their bones and muscle tissues have been used as remedies for infections, bites, cancer, heart disorders, hemorrhages, allergies, inflammation, pain and even AIDS.

Toxins of two common Asian toad species, Bufo gargarizans and Duttaphrynus melanostictus, produce the anticancer remedies known as Chan Su and Senso in China and Japan, respectively. Another preparation used to treat cancer and hepatitis, Huachansu or Cinobufacini, is regulated by the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration. In Brazil, the inner organs of the toad, Rhinella schneideri, are applied to horses to treat the parasite Habronema muscae. In Spain, extract from the toad Bufo bufo is used to treat hoof rot in livestock. In China, North and South Korea, ranchers use the meat of Bufo gargarizans to treat rinderpest.

Only a small proportion of the more than 580 species in the Bufonidae family have been screened by scientists. “In Panama, not only do we have access to an amazing diversity of amphibian species,” said Marcelino Gutiérrez, investigator at the Center for Biodiversity and Drug Discovery at Panama’s state research institute, Instituto de Investigaciones Cientificas y Servicios de Alta Tecnologia (INDICASAT), “we’re developing new mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques to make it easier and cheaper to elucidate the chemical structures of the alkaloids, steroids, peptides and proteins produced by these animals. We work closely with herpetologists so as not to further threaten populations of these species in the wild.” Their efforts to catalog chemicals produced by the Bufonidae included researchers from the University of Panama, Vanderbilt University, in Tennessee, U.S.A. and Acharya Nagarjuna University in Guntur, India.

Most of the chemicals produced by frogs and toads protect them against predators. Atelopus varius contains tetrodototoxin. Chiriquitoxin is found in Atelopus limosus, one of the first species that researches succeeded in breeding in captivity as well as in Atelopus glyphus and Atelopus chiriquiensis. An atelopidtoxin (zetekitoxin) from the Panamanian golden frog, Atelopus zeteki, appears to consist of two toxins. Toxins from a single frog skin can kill 130-1000 mice.

The golden frog, A. zeteki, Panama’s national frog, is the only species of the genus Atelopus that secretes zetekitoxins. Threatened by the chytrid fungal disease that infects the skin and causes heart attacks, with collection for the exotic pet trade and by habitat destruction, if golden frogs were to disappear, they would take this potentially valuable chemical with them.

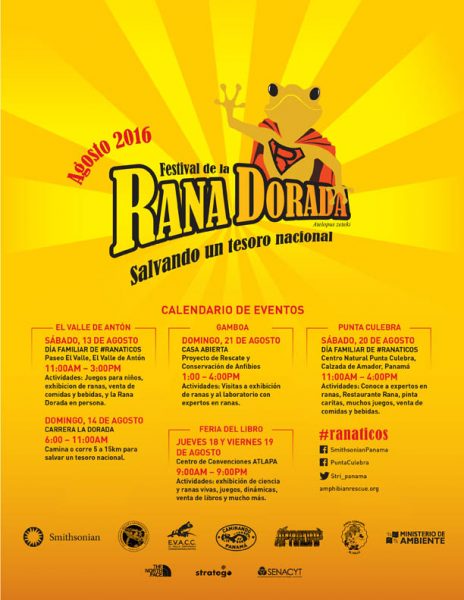

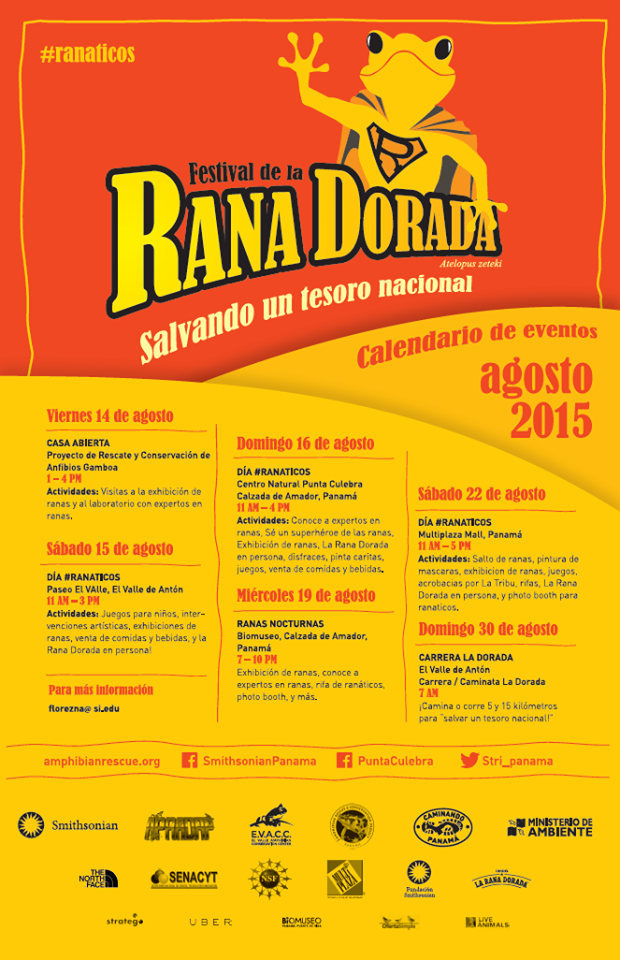

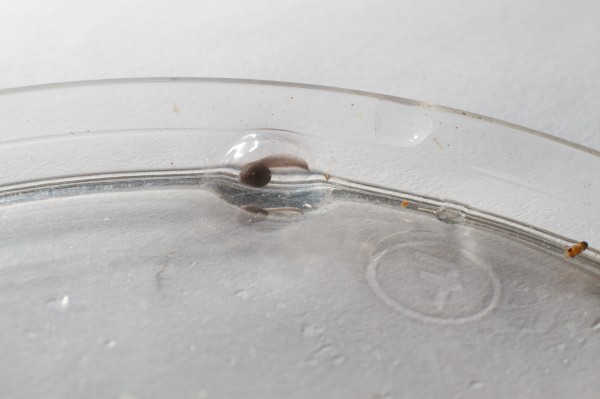

More than 30 percent of amphibians in the world are in decline. Racing to stay ahead of the wave of disease spreading across Central America, Panama is leading the way in conservation efforts. The Smithsonian’s Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation project (PARC) identified several Atelopus species in danger of extinction, and are learning how to create the conditions needed to breed them in captivity. Not only do animal caretakers at their facilities in Gamboa and El Valle, Panama experiment to discover what the frogs eat, they also recreate the proper environment the entire frog life-cycle: egg laying, egg hatching and tadpole survival, to successfully breed Atelopus. Each species has unique requirements, making it an expensive challenge to create this Noah’s ark for amphibians.

The chemical building blocks amphibians use to create toxic compounds come from sources including their diet, skin glands or symbiotic microorganisms. Toads in the genus Melanophryniscus sequester lipophilic alkaloids from their complex diet consisting of mites and ants. Researchers found that toxins found in a wild-caught species of Atelopus could not be isolated from frogs raised in captivity: another reason to conserve frog habitat and to begin to explore the possibility of releasing frogs bred in captivity back into the wild.

Learn more about amphibians by visiting the PARC blog and the Panama’s Fabulous Frogs exhibit at the Smithsonian’s Culebra Point Nature Center in Panama.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a part of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical nature and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems. Website. Promo video.

# # #

Rodriguez, Candelario, Rollins-Smith, Louise, Ibanez, Roberto, Durant-Archibold, Armando, Gutiérrez, Marcelino. 2016. Toxins and pharmacologically active compounds from species of the family Bufonidae (Amphibia, Anura). Journal of Ethnopharmacology, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.12.021