Gina Della Togna, an SCBI PhD student and native Panamanian, is one of the researchers in charge of the sperm collection procedure. (Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

With nearly one-third of all amphibian species at risk of extinction as the result of the deadly chytrid fungus, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo has taken a bold step toward preserving amphibian genes and the world’s incredible amphibian biodiversity. Researchers at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Washington, DC, have begun to collect sperm samples from the Zoo’s collection of Panamanian golden frogs (Atelopus zeteki), which are extinct in the wild.

Although researchers have collected sperm samples from other amphibian species such as Mississippi gopher frogs and leopard frogs, there are no publications detailing sperm collection methods from Panamanian golden frogs. SCBI’s colleagues at the Maryland Zoo have aided in the process, providing advice to the SCBI researchers about the method to collect the frogs’ spermatozoa using hormonal stimulations.

“We currently have three other species of Atelopus in captive assurance colonies in Panama,” said Brian Gratwicke, an SCBI conservation biologist who leads the Zoo’s amphibian conservation program to curb global amphibian declines. “If we can freeze some of their sperm, golden frogs will be a model to secure the long-term genetic integrity of other toad species in similar situations.”

Gina Della Togna, an SCBI PhD student and native Panamanian, is one of the researchers in charge of the sperm collection procedure. Even though this is still a fairly new endeavor, Della Togna said she felt that it was easy compared to collecting sperm from mammals. After hormonal stimulation, spermatozoa are excreted in the urine from the frog’s cloaca, a multipurpose opening from which feces, urine and gases are expelled. This is in contrast to mammals, which possess specialized structures for the expulsion of waste and reproduction.

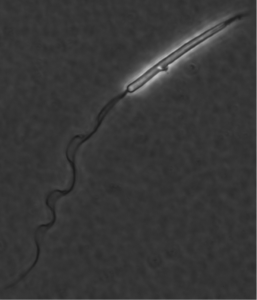

A Panamanian golden frog sperm

Although sperm collection from this species has been successful, finding the most efficient and repeatable stimulation protocol is critical. Then, identifying the right cryoprotectant and freezing method will be another challenge. Researchers suspect that the cell component most likely responsible for the movement of the sperm, called a mitochondrial vesicle, has a unique structure compared to that of other animals.

“The mitochondrial vesicle is a very fragile structure,” Della Togna said. “Protecting this structure will definitely be one of our greatest challenges.”

Even in the face of numerous challenges, the research team overseeing the sperm collection and storage of the samples remains optimistic.

Pierre Comizzoli, an SCBI gamete biologist supervising the PhD project is enthusiastic about the prospect of this endeavor and is charged with studying the complex golden frog sperm structure with Della Togna.

“It is always exciting to discover new biological mechanisms,” Comizzoli said. “Spermatozoa from each species have unique traits that needs to be well understood before developing preservation protocols.”

Other than its genetic and natural significance, the Panamanian golden frog is a meaningful symbol of culture for Panamanians. Pre-Columbian peoples used to make golden “huacas,” or sacred objects, in the image of these frogs, along with creating legends about these renowned frogs, which endure in the Panamanian countryside today, Della Togna said.

“This species does not exist anywhere else in the world,” Della Togna said. “You will find pictures and sculptures of it in local markets, in indigenous handcraft sales, and on lottery tickets, among places. Hopefully this project will help to ensure that one day you will be able to see them once again on the banks of Panamanian streams where they belong.”

–Phil Jaseph, Smithsonian’s National Zoo