Last December two researchers from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute spent two weeks in Peru surveying the Acancocha water frog (Photo by Jessica Deichmann, SCBI)

Imagine measuring the tail of a squirmy, inch-long tadpole. Now imagine doing that where the air is thin enough to make you dizzy, a hail storm is about to start and you just spent 45 minutes up to your elbows in a freezing cold stream.

Last December, Jessica Deichmann, a research scientist with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, and Ed Smith, a biologist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo’s Amazonia Exhibit, spent two weeks doing just that to complete a survey of the Acancocha water frog (Telmatobius jelskii). They were participating in a frog surveying trip for SCBI’s Center for Conservation Education and Sustainability’s Peruvian Biodiversity Monitoring and Assessment Program (BMAP). The program lends Smithsonian scientific expertise to gas and oil companies to assess the effects of development projects on local plants and animals. This information is used to improve restoration work, and reduce environmental impacts of future development. This was the third survey along the path of a natural gas pipeline constructed in 2009 that runs from the Amazon over the Andes to the Pacific Ocean—about 250 miles.

The Acancocha water frog is found only in the cold clear streams of the high-elevation Peruvian Andes. The frog is one of about 40 species researchers are surveying around the construction of this particular pipeline. Scientists chose this species because although historically it has been fairly abundant, it lives in a relatively small area with precise habitat requirements. When individuals of a species are clustered together, it’s easier to lose the entire species.

“You always worry about frogs with small geographic ranges—not just frogs, but any species,” Deichmann said.

When you think of the Peruvian Andes, you probably think of Macchu Picchu, a lush green mountainside where, as Smith jokes, “if you sit too long you have orchids growing on you.” Smith and Deichmann, however, were in a very different ecosystem called puna and sometimes nicknamed equatorial tundra. Puna is found high in the Andes, where trees no longer grow, rain is scarce, and nights are freezing. The team spent much of its time about 15,000 feet above sea level, where the air is so thin that breathing is hard until you get used to it. “For us lowland landlubbers, that alone was an exhausting business,” Smith said.

Smith and Deichmann were in a very different ecosystem called puna and sometimes nicknamed equatorial tundra. (Photo by Jessica Deichmann, SCBI)

The team—Deichmann, Smith and two Peruvian biologists—took samples at twelve sites where the pipeline crosses mountain streams. At each site, they spent about 45 minutes upstream, elbow-deep, feeling for frogs and tadpoles. For each tadpole, first, the team swabbed its mouth for a sample for chytrid testing. The team also recorded the tadpole’s body length, tail length, mass, and developmental stage, and photographed each sample before the animal was returned to the stream. They also took measurements of the stream itself. Then the team repeated the whole process downstream of the pipeline. Any one site could take five or six hours.

But Deichmann is clear that the process was worth it. “Just to find frogs and tadpoles was exciting,” she said. “Especially adults—after hours and hours in freezing cold water and your arms are purple, when you find your first frog it’s just so exciting.”

The team hasn’t processed the data yet, but their initial measurements suggest some good news: so far, they have seen no obvious effects as a result of the pipeline. However, although the team found hundreds of tadpoles, they found only 10 adult frogs in all the sample areas.

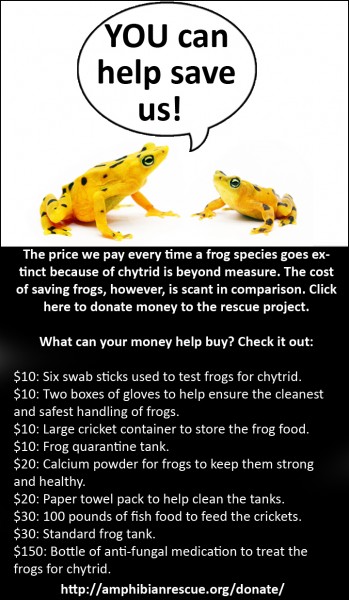

Unfortunately, that suggests chytrid is playing a role in shaping the population structure. The skin fungus follows skin keratin proteins, the amphibian equivalents of those found in human skin calluses, hair and nails. Tadpoles usually survive chytrid infection because they have keratin only around their mouths. As they develop their keratin “suit of armor,” frogs are left vulnerable to the disease that has decimated them in less than half a century.

“From metamorphosis, something called the ‘chytrid clock’ starts ticking,” Smith said. In adults, “chytrid interferes with water balance, usually in a lethal way.” Because of this, chytrid-struck populations often consist of many tadpoles and a few adults.

And according to the previous surveys, “at pretty much all the sites where frogs and tadpoles were present, chytrid was present,” Deichmann said.

At each of 132 sites, the team spent about 45 minutes upstream, elbow-deep, feeling for frogs and tadpoles. (Photo by Jessica Deichmann, SCBI)

But until they have the results from lab tests on the mouth swabs the team took, they won’t have the full picture about how the disease is affecting these populations. And chytrid isn’t the only danger these frogs face. “In a lot of our streams we were, not surprisingly but disappointingly, finding trout,” an invasive predator, Smith said.

Deichmann and Smith agree that the data they collected will be useful for conservation efforts. “Monitoring populations now gives us a baseline without which we can never know what’s changed,” Smith said. The team has a tentative follow-up survey scheduled for the dry season of 2012, during the northern hemisphere’s summer. Deichmann hopes that the data from this December’s trip will allow the program to modify the survey protocol to make sure future trips are gathering the most helpful data possible.

And of this expedition? “It was an amazing trip,” Deichmann said. “The habitats are stunning, the scenery is stunning. You’re at the top of the world.”

—Meghan Bartels