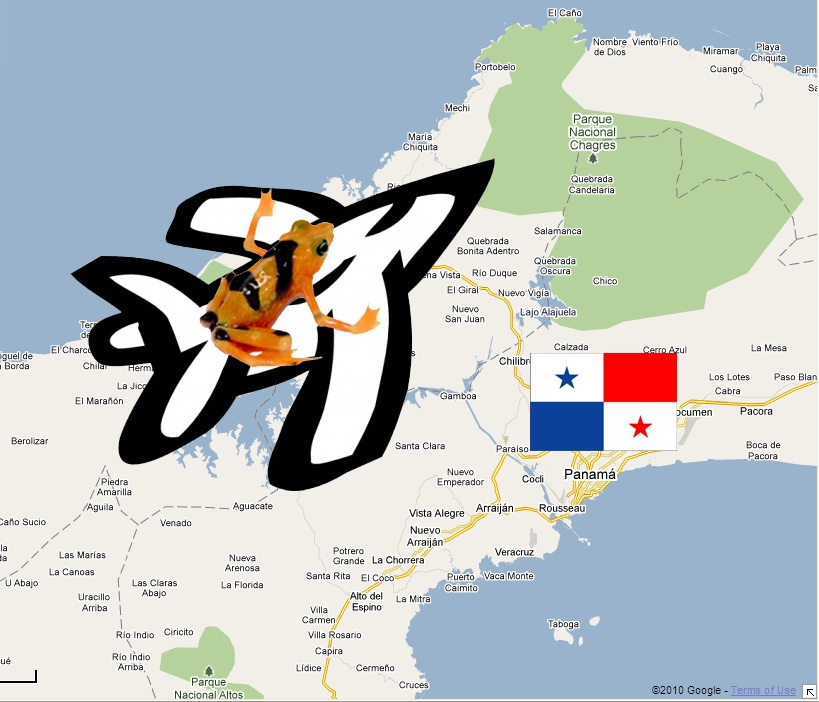

Researchers collected these dead frogs from sites where the fungus is moving through. (Photo credit: Karen Lips, University of Maryland)

Booo! Halloween’s over but ghost stories linger. In Panama, holiday season has begun! Nov. 3 marked the start of a long string of holidays–Independence from Colombia and from Spain this month, Mother’s Day, Chaunukah and Christmas in December, summer vacation for kids during the dry season, and ending up with Carnival festivities in February and back to school in March.

Yesterday my family piled into the car for the day-long drive up into the Chiriqui highlands near the border of Panama and Costa Rica.

We slept very well last night in the cool mountains where it’s extremely quiet compared to our home on the border of Soberania National Park in the lowlands where they say that the night time forest sound reaches 50 decibels–and a big part of that sound comes from frogs.

For some reason that no one understands, the chytrid fungus pathogen doesn’t seem to kill frogs in the lowlands, where it is sometimes found, but it decimates all amphibian populations along highland streams.

Earlier this month I had the wonderful opportunity to take an interpretation course offered by the National Association for Interpretation as part of a USAID tourist guide training program organized by Panama’s Association for Sustainable Tourism (APTSO). Each of the student guides was asked to share a story that they tell visitors to Panama that touches their hearts.

Carlos Fonseca, a young guide from Chiriqui, told that he and his brother used to spend summer days playing along streams in the highlands where they loved to find frogs…colorful frogs with pale white underbellies and even glass frogs that you can see through! About ten years ago, the chytrid epidemic passed through, and now the kids who play there don’t even know that there were frogs there.

Insects and birds dominate a cloud forest soundscape that used to ping and croak.

So, we’ll go for long walks in the woods on our weekend trip–we will see rainbows and maybe even a resplendant quetzal–and we’ll keep our eyes open for survivors–the few frogs that either managed to escape or were resistant to the disease.

Due to the vision of researchers like Karen Lips, from the University of Maryland, who first saw the fungus coming into Panama from Costa Rica, Roberto Ibanez, from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Brian Gratwicke from the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, a rescue effort was mounted to save Panama’s frogs. Now, with support from Panama’s Environmental Authority (ANAM) and Summit Nature Park in Panama and eight other partner institutions in the United States, the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation project rescues frogs in Eastern Panama where the fungus hasn’t been yet. It is one of the few examples of proactive conservation of species that otherwise would be doomed, and, to that end, offers a kind of hope that is rare in this world.

–Beth King, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute