The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has established an assurance colony for two species endemic to the Darien, including the Toad Mountain harlequin frog (Atelopus certus), shown here. (Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

Smithsonian scientists have confirmed that chytridiomycosis, a rapidly spreading amphibian disease, has reached a site near Panama’s Darien region. This was the last area in the entire mountainous neotropics to be free of the disease. This is troubling news for the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, a consortium of nine U.S. and Panamanian institutions that aims to rescue 20 species of frogs in imminent danger of extinction.

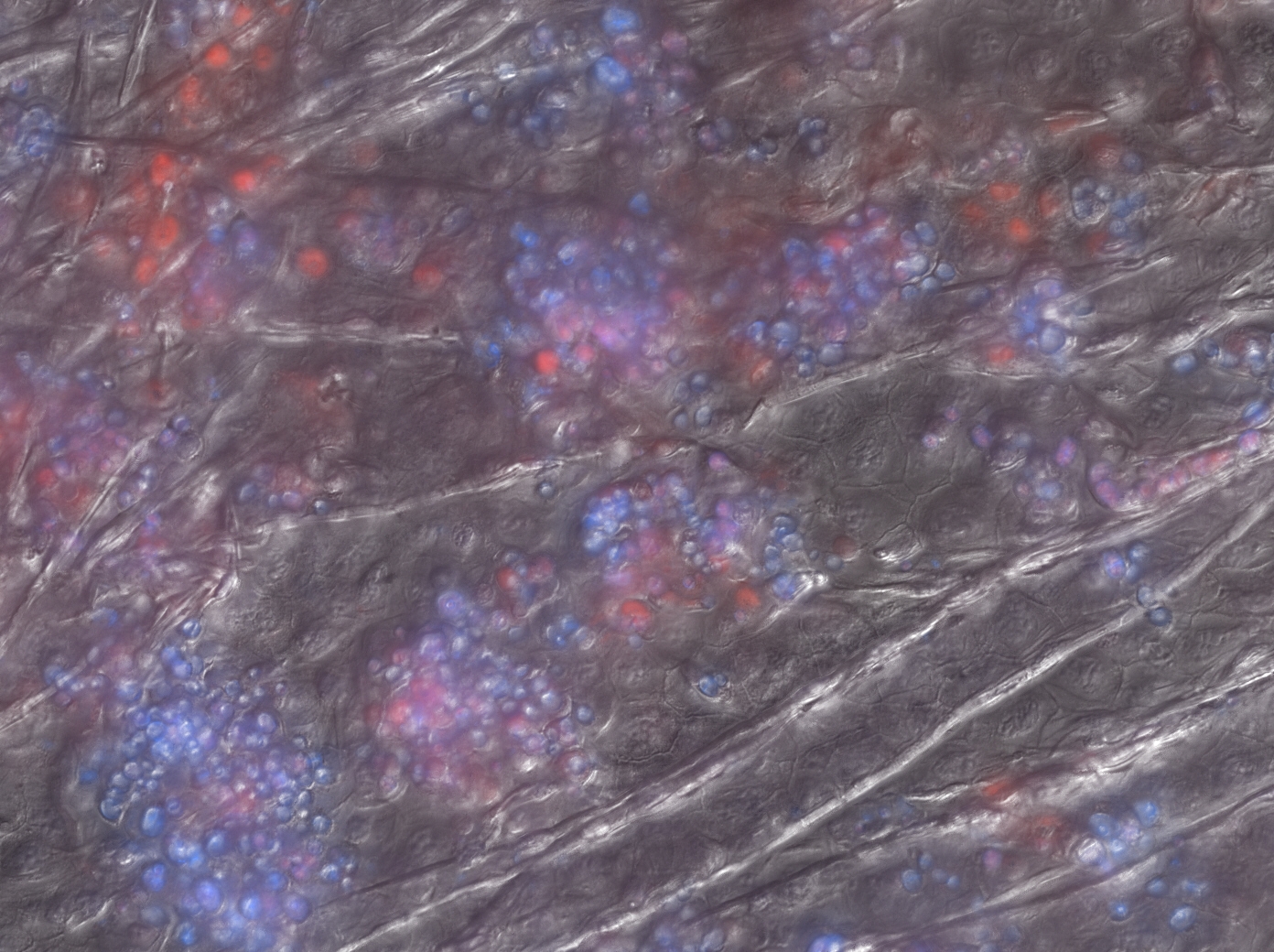

Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines or even extinctions of amphibian species worldwide. Within five months of arriving at El Cope in western Panama, chytridiomychosis extirpated 50 percent of the frog species and 80 percent of individuals.

“We would like to save all of the species in the Darien, but there isn’t time to do that now,” said Brian Gratwicke, biologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and international coordinator for the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project. “Our project is one of a few to take an active stance against the probable extinction of these species. We have already succeeded in breeding three species in captivity. Time may be running out, but we are looking for more resources to take advantage of the time that remains.”

The Darien National Park is a World Heritage site and represents one of Central America’s largest remaining wilderness areas. In 2007, Doug Woodhams, a research associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, tested 49 frogs at a site bordering the Darien. At that time, none tested positive for the disease. In January 2010, however, Woodhams found that 2 percent of the 93 frogs he tested were infected.

“Finding chytridiomycosis on frogs at a site bordering the Darien happened much sooner than anyone predicted,” Woodhams said. “The unrelenting and extremely fast-paced spread of this fungus is alarming.”

The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project has already established captive assurance colonies in Panama of two priority species endemic to the Darien—the Pirre harlequin frog (Atelopus glyphus) and the Toad Mountain harlequin frog (A. certus). In addition, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo maintains an active breeding program for the Panamanian golden frog, which is Panama’s national animal. The Panamanian golden frog is critically endangered, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and researchers have not seen them in the wild since 2008.

Chytridiomycosis is a rapidly spreading amphibian disease that attacks the skin cells of amphibians (shown here) and is wiping out frog species worldwide. (Doug Woodhams, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute)

“We would like to be moving faster to build capacity,” Gratwicke said. “One of our major hurdles is fundraising to build a facility to house these frogs. Until we jump that hurdle, we’re limited in our capacity to take in additional species.”

Nearly one-third of the world’s amphibian species are at risk of extinction. While the global amphibian crisis is the result of habitat loss, climate change and pollution, chytridiomycosis is at least partly responsible for the disappearances of 94 of the 120 frog species thought to have gone extinct since 1980.

“These animals that we are breeding in captivity will buy us some time as we find a way to control this disease in the wild and mitigate the threat directly,” said Woodhams, who was the lead author of a whitepaper Mitigating Amphibian Disease: strategies to maintain wild populations and control chytridiomycosis. This paper, published in Frontiers in Zoology, systematically reviews disease-control tools from other fields and examines how they might be deployed to fight chytrid in the wild. One particularly exciting lead in the effort to find a cure is that anti-chytrid bacteria living on frog skin may have probiotics properties that protect their amphibian host from chytrid by secreting anti-fungal chemicals. Woodhams recently discovered that some Panamanian species with anti-chytrid skin bacteria transmit beneficial skin chemicals and bacteria to their offspring. The paper, Social Immunity in Amphibians: Evidence for Vertical Transmission of Innate Defenses, was published in Biotropica in May.

“We are all working around the clock to find a cure,” Gratwicke said. “Woodhams’ discovery that defenses can indeed be transferred from parent to offspring gives us hope that if we are successful at developing a cure in the lab, we may find a way to use it to save wild amphibians.”

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute serves as an umbrella for the Smithsonian Institution’s global effort to understand and conserve species and train future generations of conservationists. Headquartered in Front Royal, Va., SCBI facilitates and promotes research programs based at Front Royal, the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and at field research stations and training sites worldwide.

# # #

Media only: contact Lindsay Renick Mayer, Smithsonian’s National Zoo, 202-633-3081