This video celebrates Atelopus manauense, a small recently described harlequin toad species from Manaus in central Amazonia, Brazil. The music video was made by JacanaJacana as part of a National Geographic grant to foster interdisciplinary conservation collaboration.

Jambato Negro. Jacana Jacana y Grecia Albán feat Alianza Jambato

This video was a collaboration between Jacana Jacana and Centro Jambatu as part of a National Geographic Meridian Grant to Re:Wild to help National Geographic Explorers collaborate as part of the Atelopus Survival Initiative.

The Golden Frog Song

Enjoy this performance of “La Rana Dorada” one of four original songs by National Geographic explorer Jani Benavides of Jacana Jacana as part of the Atelopus Survival Initiative and National Geographic Meridian Grant meeting hosted by the Fundacion Atelopus and Re:wild in Sierra Santa Marta.

Insectarium

Construction of our new insect facility was completed and fire suppression systems installed. This new 1,600 square feet insectarium has two climate-controlled rooms that can be maintained at different temperatures, allowing a diversity of food items with varying sizes and nutritional properties to meet the needs of our diverse amphibian collection. A huge thanks to the STRI Office of Facilities and Engineering who oversaw this project and to the many individual donors, the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, the Houston Zoo, the Holtzman Foundation, the Shared Earth Foundation for enabling us to complete it.

Under the leadership of Nancy Fairchild and Jennifer Warren, our insect production capacity is now one of the incredible success stories of our project. There are no local sources of captive-reared insects, so we are 100% reliant on our own production and have redundant capacity to accommodate any unexpected changes in the populations of the various springtails, fruitflies, crickets, pantry moths, soldier flies, cockroaches and earthworms that we produce. This team has also conducted original research to develop gutloading propocols for springtails and demonstrated improved outcomes of juvenile frogs reared on this nutritionally supplemented prey, compared to their normal yeast-based diets.

First release trial of Atelopus limosus shows that animals rapidly recover a wild-type skin microbiome.

In 2017, Virginia Tech PhD students Angie Estrada and Daniel Medina conducted the first release trial of captive-bred Limosa Harlequin frogs at the Mamoni Valley Preserve. Their study aimed to closely observe how 1-year-old captive-bred animals would transition from captive conditions back into the wild. To soften the blow of the changing conditions, and to allow the researchers to capture the frogs again, they designed 30 square shaped mesocosms from plastic mesh. In reintroduction biology placing animals in a temporary field enclosure prior to release is known as a soft release. They filled the bottom layer with leaf litter collected from the forest floor that was rich in leaf-litter invertebrates, a diet quite different from the crickets and fruit-flies they are usually fed by staff at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Center. Each mesocosm housed a single animal that was monitored daily for a month and weighed and swabbed weekly.

It is known that captivity can alter skin microbiomes of amphibians and other captive animals, and that this is an important component of amphibian immune defenses. This study found that wild and captive Atelopus limosus had very different microbiomes, but that after a month living in mesocosms, the skin microbiome had rapidly changed to resemble the microbiome of wild individuals. One concern about bringing animals into captivity for prolonged periods is that animals might lose symbiotic microbes that help them to survive in the wild, which might reduce the fitness of captive-bred animals, but this study found that the skin microbiome was rapidly rewilded.

The mesocosms were a useful tool that protected the animals from larger predators, though one was killed by army ants. Female animals lost body condition more rapidly than males, but at the end of the trial their condition resembled that of wild-caught animals. About 15% of the animals became infected with the amphibian chytrid fungus in the first month compared to 13-27% Bd prevalence in wild amphibian community.

Estrada, A., Medina, D; Gratwicke, B, Ibáñez, R, Belden, L (2022) Body condition, skin bacterial communities and disease status: Insights from the first release trial of the Limosa harlequin frog, Atelopus limosus. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0586

It’s world frog day and we are celebrating Harlequin frogs!

There are more than 100 brightly colored Harlequin toads in the genus Atelopus, and 90% of them are threatened with extinction, and are highly susceptible to the deadly amphibian chytrid fungus. The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is working to save 5 critically endangered Panamanian Atelopus species from extinction and is part of a a larger global conservation effort called the Atelopus Survival Initiative.

The Panamanian Golden Frog Atelopus zeteki is a national symbol of Panama, and one of the most recognizable harlequin frogs, but they are extinct in the wild. Fortunately this species breeds in 50 AZA zoos and aquaria and at the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project. The National Zoo has conducted intense research efforts to develop a probiotic cure for the amphibian chytrid fungus, but these efforts have not been successful to date.

As its name suggests the variable harlequin frog comes in lots of different colors, from solid gold like Panamanian golden frogs to brown, green or orange! This species is a very close genetic sister species to the Panamanian golden frog Atelopus zeteki, and both species are referred to as golden frogs. Atelopus varius that have survived the amphibian chytrid epidemic seem to have experienced recent migration or gene flow into their populations, indicating the potential for genetic rescue in this species. We are actively exploring this idea with a grant from Revive and Restore.

Some people call Atelopus the stub-foot toads because the etymology of word ‘Atelopus’ translates to “incomplete end of toe”. However, a more commonly used name for this group of animal is harlequin toads because their bright patterns and colors are reminiscent of a court jester costume. Atelopus are true toads because they are in the toad family Bufonidae and while they don’t resemble the more familiar brown, warty toad species, they do lay the double-stranded strings of eggs characteristic of toads. All toads are also members of the tail-less amphibian order Anura (Frogs), so sometimes they are also called harlequin frogs.

Male harlequin toads can be very clingy, hanging on to females for up to 100 days before they lay their eggs, it is a kind of mate-guarding behavior. Egg laying can take 8-9 hours, and once the eggs have been laid the males swiftly lose interest and abandon the females fairly quickly.

Limosa harlequin frogs are found in central Panama and has declined rapidly due to the amphibian chytrid fungus. Researchers at the Pamama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project and Virginia Tech conducted the first release trials for this species. We reared captive frogs and released them to understand how animals transition from captive conditions to the wild and attached tiny radiotransmitters to the frogs to understand where they disperse.

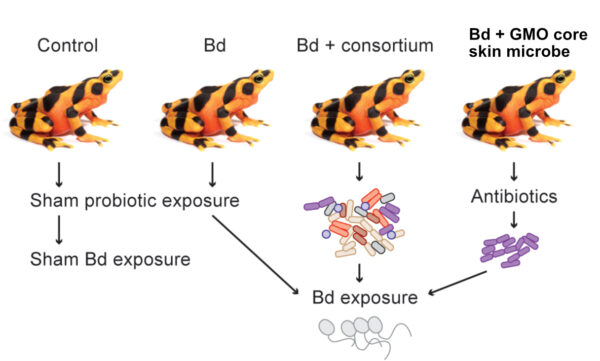

New study genetically engineers skin bacteria in attempt to control the amphibian chytrid fungus

In our latest research project the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the Synthetic Biology Center Dept of Biological Engineering at MIT collaborated to test two technically challenging ideas using probiotic approaches to protect highly susceptible amphibians from the amphibian chytrid fungus (Bd). The paper was recently published in the Journal ISME Communications. We isolated a core frog skin bacteria that is found in high numbers on most golden frogs and genetically engineered it to produce an antifungal metabolite that kills the pathogen called violacein. By using a bacterium well-adapted to thrive on the frogs’ skin, that also produces antifungal metabolites we hoped to protect the frogs from disease. We were able to genetically modify one core skin microbe to produce violacein, but it did not persist well on the frog skin and was displaced after 4 weeks by the unmodified native bacteria strain. Treating the frogs with this genetically modified core skin microbe did not prevent the frogs from Bd or reduce infections.

In this new experiment, we tested two new probiotic strategies to protect frogs from Bd. 1) Using a consortium of antifungal bacteria isolated from the frogs 2) Using a core skin microbe found on all golden frog skin that was genetically modified to produce antifungal metabolites.

In a second experimental group we mixed a consortium of seven antifungal bacteria that had been isolated from golden frog skin and supplemented the skin microbiome with these potentially beneficial microbes. Three of the seven bacteria persisted on the skin after 4 weeks, but this probiotic treatment also failed to protect the frogs from disease. While these results are disappointing, we were able to successfully test two technically-challenging ideas that have been discussed in the amphibian conservation community for many years. Furthermore, this research illustrates some of the challenges we still face in understanding and manipulating microbiomes and in using synthetic biology to solve real environmental problems.

The research was led by Dr. Matthew Becker, Rob Fleischer and Brian Gratwicke (Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute) and Dr. Jennifer Brophy and Christopher Voigt (Synthetic Biology Center Dept of Biological Engineering at MIT). Other collaborators include Ed Bronikowski, Matthew Evans, Blake Klocke, Elliot Lassiter, Alyssa W. Kaganer, Carly R. Muletz-Wolz (Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute). Kevin Barrett (Maryland Zoo in Baltimore), Emerson Glassey & Adam J. Meyer (MIT). The work was funded by individual donors, the Smithsonian Institution Competitive Grants Program for Science, the Smithsonian Postdoctoral Fellowship, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of International Conservation Amphibians in Decline Fund, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Biological Robustness in Complex Settings program. The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore and the AZA Golden Frog Species Survival Program provided surplus-bred animals for research.

By Brian Gratwicke

Becker, M.H., Brophy, J.A.N., Barrett, K, Bronikowski, E., Evans, M., Glassey, E., Klocke, B. Lassiter, E., Meyer, A.J., Kaganer, A.W., Muletz-Wolz, C.R., Fleischer, R.C., Voigt, C.A., and Gratwicke, B. Genetically modifying skin microbe to produce violacein and augmenting microbiome did not defend Panamanian golden frogs from disease. ISME Communications

In unprecedented effort, more than 40 organizations from 13 countries come together to protect and restore harlequin toads, the jewels of South and Central America, hard hit by a deadly amphibian disease

With the formation of the Atelopus Survival Initiative (ASI)–a new alliance of more than 40 organizations from 13 countries–comes a new day for harlequin toads, the jewels of South and Central America’s forests and creeks and a group of amphibians hardest hit by the deadly chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd).

While amphibian researchers and conservationists have worked for many years to save harlequin toads (which make up the Atelopus genus) and groups of species in individual countries, the ASI is bringing them together for the first time to pool the resources, decades of experience and knowledge necessary to prevent the extinction of the entire genus of harlequin toads across the region where these species still survive.

“As an incredibly diverse group of amphibians facing a number of threats, harlequin toads require innovative solutions coming from a diverse group of individuals and organizations with different expertise, knowledge and capacities,” said Lina Valencia, ASI founder, co-coordinator of the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group Atelopus Task Force and Andean countries coordinator for Re:wild, one of the primary ASI conveners. “More than ever before, we need a constellation of champions working together to bring harlequin toads back from the brink of extinction. The ASI underscores the vital need to implement on-the-ground conservation actions that will mitigate the main threats to this beautiful group of amphibians.”

Over the past few decades, many harlequin toad species have suffered severe population declines and extinctions throughout their range. Today, of the 94 harlequin toad species that have been assessed by the IUCN, 83 percent are threatened with extinction, while about 40% of Atelopus species have disappeared from their known homes and have not been seen since the early 2000s, despite great efforts to find them. Four harlequin toad species are already classified as extinct, according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, but this number is likely higher.

The fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) causes the lethal disease chytridiomycosis, which has resulted in amphibian declines all around the world, including in South and Central America, Australia and the western United States. Although Bd may likely be the primary driver of these declines, a number of other threats are exacerbating the precipitous drops in population numbers. This includes habit destruction and degradation (as the result of animal agriculture, logging, mining and infrastructure development), the introduction of invasive species such as the rainbow trout that prey on harlequin toad tadpoles, pollution, illegal collection for the pet trade, and the effects of climate change.

The ASI and its members, including governments, local communities and Indigenous peoples, will collaboratively address each of these threats–and new ones as they arise–across the genus’s full range, taking into account the social, political and cultural realities of each of the 11 countries where harlequin toads are found.

“With their beautiful songs and unique lifestyles, amphibians are among the most extraordinary animals on Earth, and among them, harlequin toads stand out for their amazing colors,” said Luis Fernando Marin da Fonte, coordinator of the ASI and director of partnerships and communications for the Amphibian Survival Alliance. “But these colorful and delicate jewels are becoming increasingly rarer. Harlequin toads must be protected not only because of their beauty and uniqueness, but also because of their intrinsic value and biological, ecological and even cultural importance.”

The initiative’s newly developed Harlequin Toad (Atelopus) Conservation Action Plan (HarleCAP) provides the roadmap for conserving and restoring harlequin toads as a genus and their habitat. The action plan’s goals, which ASI aims to achieve by 2041 (the 200th anniversary of the description of the genus Atelopus), include:

- developing and implementing innovative methods to mitigate chytrid’s impacts on harlequin toad populations and better understanding why some species are less susceptible to the effects of chytrid;

- protecting and restoring harlequin toads’ forests and watersheds;

- creating and maintaining conservation breeding programs;

- searching for species that are lost to science and filling in other gaps in scientific knowledge about harlequin toads;

- sharing stories that will transform harlequin toads into symbols of hope for the region and the world and a flagship for conservation success, and demonstrate a commitment to the conservation of harlequin toads;

- ensuring the Atelopus conservation network has the technical, logistical, and financial support to secure the long-term conservation of harlequin toads

“The establishment of collaborative initiatives at the international and regional level is essential to coordinate efforts and obtain tangible results that have an efficient and real impact on the conservation of an endangered species,” said Gina Della Togna of the Universidad Interamericana de Panamá, Panamá. “The Atelopus Survival Initiative is a concrete example, which not only aims to conserve one species, but an entire genus, perhaps the most threatened by the global amphibian extinction crisis.”

Harlequin toads are found from Costa Rica in the north to Bolivia in the south, and Ecuador in the west and French Guiana to the east. They are known as the jewels of South and Central America in part because of their beautiful and varied colors, which range from orange, green, yellow, brown, black, red, and sometimes even purple. They are celebrated in a number of Latin American cultures, including Indigenous cultures, and across entire countries, like in Panama, where the national animal is the Panamanian golden toad.

Like other amphibians, harlequin toads support healthy ecosystems. Their tadpoles depend on clean water and, because of this, the presence of harlequin toads indicates better quality water in an ecosystem, while their decline or absence is often the first sign of an ecosystem in trouble.

“Protecting and restoring harlequin toads and their habitats will also benefit the species that share the ecosystems in which they live and that provide water to tens of millions of people, and ultimately all life on Earth,” Valencia said. “And we’re hoping that the ASI will be a successful model that conservationists can emulate for other groups of threatened species.”

The Atelopus Survival Initiative includes national and international conservation groups, zoos, captive breeding centers, academic institutions, governments and local communities. Its current members represent the following organizations: Amphibian Ark, Amphibian Survival Alliance, Asociación Pro Fauna Silvestre – Ayacucho, Bioparque Municipal Vesty Pakos, Bolivian Amphibian Initiative, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Centro de Conservación de Anfibios AMARU, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios/Fundación Jambatu, CORBIDI, DoTS, El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center Foundation, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Florida International University, Fort Worth Zoo, Fundación Atelopus, Fundación Zoológica de Cali, Universidad del Tolima (GHEE), Grupo de Trabajo Atelopus Venezuela, Image Conservation, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Instituto Venezolano de, Investigaciones Científicas, Ministerio del Ambiente de Perú, MUBI (Museo de Biodiversidad del Perú), Parque Explora, Parque Nacional Natural Puracé, Photo Wildlife Tours, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Re:wild, San Diego State University, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Trier University, Universidad de Antioquia, Universidad de Costa Rica, Universidad de los Andes, Universidad del Tolima, Universidad del Magdalena, Universidade Federal do Pará, Universidad Nacional, Universidad Interamericana de Panamá, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, University of Nevada, Reno, University of Notre Dame, University of Pittsburgh, WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society), WCS Colombia, Zoológico Cuenca Bioparque Amaru

An Amphibian Ark in the time of Pandemic

New publication! IUCN Guidelines for amphibian reintroductions and other conservation translocations

An exciting new publication has just been released by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) of best practice guidelines for a wide range of amphibian conservation translocations. The project was many years in development through the coordinated effort of numerous translocation specialists across the globe, but the project the led by the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project’s post-doctoral research fellow Dr. Luke Linhoff. The guidelines cover the reasons for conducting amphibian translocations, pre-translocation planning and risk assessment, and also cover important topics such as disease, welfare, human social dimensions, post-release monitoring and reporting results.

A free digital download and more information on the guidelines can be found at: https://www.iucn-amphibians.org/iucn-guidelines-for-amphibian-reintroductions-and-other-conservation-translocations/