The ability of certain Panamanian species to survive will depend on the ability of the rescue project to perfect specialized care for the individual species. (Photo by Lindsay Renick Mayer, Smithsonian

When we talk about frog diversity, we always mention how many species there are, or how they are found all over the world. We say how much frogs vary in size, or how colorful they can be. This is all true: there are more than 4,900 frog species, found on every continent, ranging from ½-inch long to more than a foot, that come in every color of the rainbow. It makes sense, then, that frogs are just as diverse during their other stages of the life cycle. Tadpoles, in fact, are among the most diverse vertebrates on Earth and are themselves morphologically and behaviorally unique from their adult counterparts.

Special Adaptations

Depending on the species, tadpoles can stay in the larval stage from eight days to two years, and vary in length from 1 to 4 inches. Overall, there is greater tadpole diversity in the tropics, but variations occur within habitats, as well. Even tadpoles with the same feeding habits can have diverse mouth shapes or behaviors. For example, tadpoles of the Asian horned frog (Megophrys montana) have an upturned mouth because they eat from the surface. Recently, however, scientists have observed a Honduran tadpole called Duellmanohyla soralia that also eats from the surface, but has a mouth in the more traditional spot. Instead, the Duellmanohyla soralia turns its body upside-down to reach the surface.

“We see tadpoles solving the same problems of survival in different ways,” says Dr. Roy McDiarmid, an amphibian zoologist and tadpole expert at the National Museum of Natural History. “This is where their diversity derives from.”

These variations show how tadpoles’ features are shaped largely by their surrounding environments. For example, tadpoles seem especially good at responding to strong predator presence. Over time tadpoles can grow their tails longer and deeper if there are numerous predators, allowing them to swim faster and look bigger. For European common frog (Rana temporaria) tadpoles, longer tails increase their chances of escape from predators up to 30 percent, according to the Institute of Zoology.

Like tail length, other adaptations can protect tadpoles from being eaten. While the majority of tadpole species have brown or faded coloration, several are multicolored. Contrary to its name, Cope’s gray tree frog (Hyla chrysoscelis) tadpoles grow red tails in response to the presence of dragonflies. Called aposematism, vibrant colors make these tadpoles appear larger or distasteful to their predators.

Researchers have only recently discovered other survival mechanisms that tadpoles have developed. In 2006, scientists discovered that if attacked, red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callidryas) embryos can hatch themselves within seconds and escape into the water below. These embryos can interpret vibrations on the water with astonishing precision.

“It turns out that when a snake bites into a gooey mass, all the embryos try to wiggle free,” Karen Warkentin, a biologist working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, told National Geographic. “A wasp’s more focused attack prompts only neighboring eggs to hatch. And a rainstorm triggers nothing at all.”

Other recent research has looked at tadpole sensory input, such as smell and sound. In 2009, researchers at the University of California Davis determined that wood frog (Rana sylvatica) tadpoles can “smell” their primary predator, the salamander. The “odor” of a salamander in the water caused tadpoles to freeze. The strength of the scent determined how long the tadpoles remained still. In 2010, Dr. Guillermo Natale discovered the first evidence of aural larva communication. Natale heard tadpoles of the Bell’s horned frog (Ceratophrys ornate) “screaming” underwater when a threat was present.

Discovery

The amount of tadpole diversity rivals that of their adult life forms. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

New and unpredictable tadpole discoveries continue to go on worldwide. For example, biologists at the Australian Museum in Sydney recently discovered that tadpoles of the vampire flying frog (Rhacophorus vampyrus) have small black fangs, instead of traditional mouthparts. In general, scientists estimate that more than 1,000 frog species have yet to be discovered, not to mention all the intricacies of their life stages.

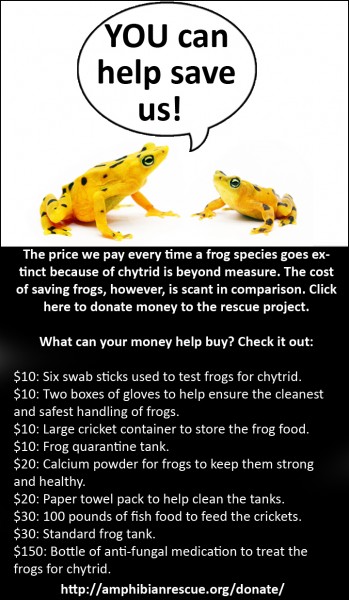

Tadpoles are also essential for understanding the dramatic decline in frog populations. Chytrid, the epidemic that has affected 30 percent of the world’s amphibian population, is the lead cause of this decline. In tadpoles, chytrid only infects the keratin around their mouths. However, as they metamorphose into frogs, chytrid fatally spreads throughout their bodies. By studying tadpoles, we can better understand how frogs contract and carry chytrid.

“When frog species are disappearing like they are, you would want to know what’s going on at each stage of the life cycle, egg to larva to juvenile to adult–everything,” McDiarmid says.

The Challenges of Breeding

For the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, every tadpole means the chance for a species to survive. But because many of the rescue project’s priority species have never been kept or bred in captivity before, rearing tadpoles can mean a steep learning curve.

“Breeding frogs isn’t just about putting a male and female together and hoping for eggs,” said Lindsay Renick Mayer, spokesperson for the rescue project. “It’s about specialized husbandry for each individual species among a diverse array and unfortunately for some of these species we’re learning those skills even as the species dwindles down to just a few remaining individuals. Whether these species are one day returned to the wild depends on the rescue project’s success in perfecting the variety of care in a short period of time.”

–Nadia Hlebowitsh, Smithsonian’s National Zoo