Once common along highland streams from western Costa Rica to western Panama, the variable harlequin frog is endangered throughout its range, decimated by a disease caused by the amphibian chytrid fungus. On Jan. 17, Smithsonian researchers released approximately 500 frogs at Cobre Panama concession site in Panama’s Colon province as a first step toward a potential full-scale reintroduction of this species. This release trial is included in Cobre Panama’s biodiversity conservation plan as an important part of their environmental commitments.

Composite image showing variation in coloration within this population of frogs

The variable harlequin frog, Atelopus varius, takes its name from the variety of neon colors—green, yellow, orange or pink—juxtaposed with black on its skin. In order to monitor the released frogs over time, 30 are wearing miniature radio transmitters. The scientific team also gave each frog an elastomer toe marking that glows under UV light to mark individuals as part of a population monitoring study.

“Before we reintroduce frogs into remote areas, we need to learn how they fare in the wild and what we need to do to increase their chances of survival in places where we can monitor them closely,” said Brian Gratwicke, international coordinator of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation project (PARC) at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. “Release trials may or may not succeed but the lessons we learn will help us to understand the challenges faced by a frog as it transitions from captivity into the wild.”

Heidi Ross and her team at our facilities in the Nispero Zoo successfully bred and reared these animals for the release trial

Variable harlequin frogs are especially sensitive to the amphibian chytrid fungus, which has pushed frog species to the brink of extinction in Central America. PARC brought a number of individuals into the breeding center between 2013 and 2016 as chytrid continued to impact wild populations.

The field team all assembled with frogs ready for the release trial

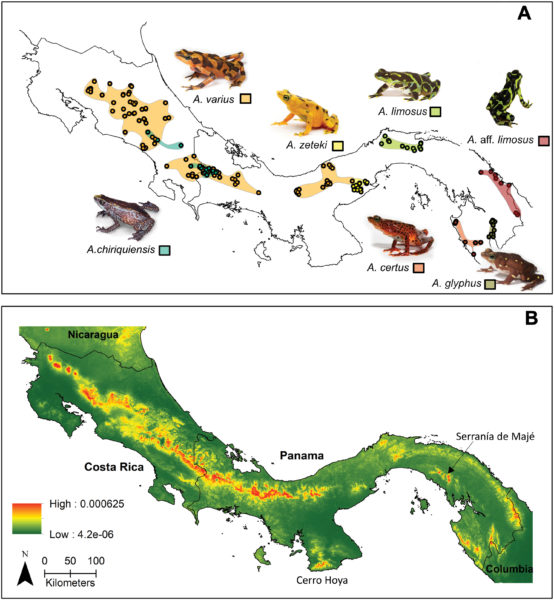

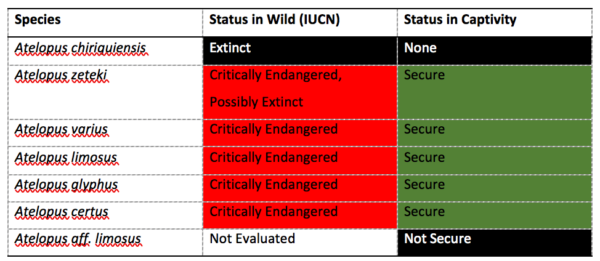

“The variable harlequin frog is one of the closest relatives of Atelopus zeteki, Panama’s iconic golden frog, another target species in our captive breeding program,” said Roberto Ibañez, PARC project director at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. “We’ll be monitoring the surrounding amphibian community and the climate at this site, and comparing this to the amphibian community at another, control site. This kind of intensive monitoring will help us to understand disease dynamics in relation to the release trials”

One of our Atelopus varius wearing a mini radio-transmitter

PARC hopes to secure the future for this and other endangered amphibians by reintroducing animals bred in captivity according to an action plan developed with Panama’s Ministry of the Environment and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and other stakeholders. “It took us several years to learn how to successfully breed these frogs in captivity,” said Ibañez. “As the number of individuals we have continues to increase, it provides new research opportunities to understand factors influencing survival that will ultimately inform long-term reintroduction strategies.”

The PARC project thanks Cobre Panama, National Geographic Society, Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and The WoodTiger Fund for their generous support.

PARC is a partnership between the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, the Houston Zoo, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Zoo New England. It has two facilities in Panama: the Gamboa Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Center at STRI and the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center at El Nispero. Combined, these facilities have a full-time staff caring for a collection of 12 endangered species.

SCBI plays a leading role in the Smithsonian’s global efforts to save wildlife species from extinction and train future generations of conservationists. SCBI spearheads research programs at its headquarters in Front Royal, Va., the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and at field research stations and training sites worldwide. SCBI scientists tackle some of today’s most complex conservation challenges by applying and sharing what they learn about animal behavior and reproduction, ecology, genetics, migration and conservation sustainability.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.

Panamanian toads Rhinella centralis are distinguished by their dorsal skin covered with pointed warts. They are common along the Pacific coastal areas, often in urban areas around Panama City and small towns, and form large choruses on rainy nights. The small but strongly swollen poison glands on their heads secrete a white toxic goop. This effective defense mechanism makes predators spit them out, or froth at the mouth, vomit and it may even kill them if they try to eat the toad.

Panamanian toads Rhinella centralis are distinguished by their dorsal skin covered with pointed warts. They are common along the Pacific coastal areas, often in urban areas around Panama City and small towns, and form large choruses on rainy nights. The small but strongly swollen poison glands on their heads secrete a white toxic goop. This effective defense mechanism makes predators spit them out, or froth at the mouth, vomit and it may even kill them if they try to eat the toad.