Cute Amphibian of the Week: January, 28, 2013

The hellbender has the distinct honor of being the largest salamander in the United States, growing as large as two feet long. It can be found in rocky, clear creeks and rivers, usually where there are large rocks for shelter. Its mottled appearance allows the hellbender to almost perfectly blend into its surroundings, making it quite the crafty salamander. Despite its name, this species is not a fan of warm water and strictly avoids water with temperatures above 68 o Fahrenheit/20 o Celsius.

The principal threat to this species is habitat degradation since it is a habitat specialist with little tolerance of environmental change. While it may seem like the sensitive type, do not be fooled; this species knows how to defend itself when push comes to shove. Hellbenders produce skin secretions that are likely unpalatable to predators and lethal in mice. At the current time the species is listed as near threatened by the IUCN.

Follow the Smithsonian National Zoo’s hellbender work at http://www.salamanderscience.com/.

Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

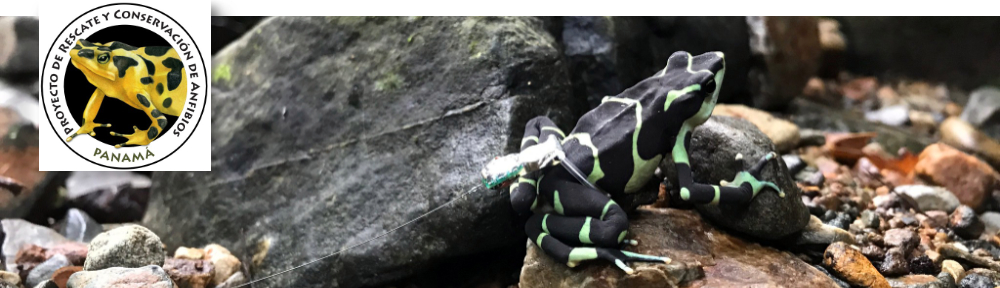

Every week the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project posts a new photo of a cute frog from anywhere in the world with an interesting, fun and unique story to tell. Be sure to check back every Monday for the latest addition.

Send us your own cute frogs by uploading your photos here: http://www.flickr.com/groups/cutefrogoftheweek/