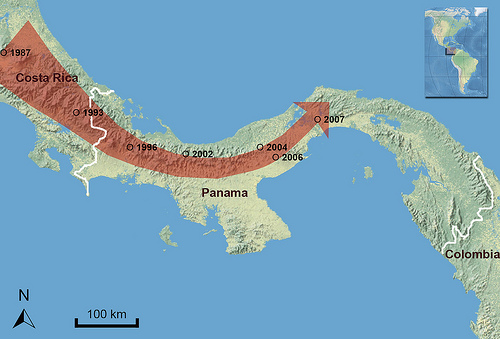

It’s difficult to communicate the extent of the amphibian crisis using only numbers. The 2008 global amphibian assessment lists 120 potentially extinct species and 39 extinct amphibian species. Of these, 94 had chytridiomycosis listed as a likely threat associated with their disappearance. Most of the missing species are from Central and South America, but we are also losing species from North America, the Caribbean, Australia, the Middle East, Asia and Australia.

It’s difficult to communicate the extent of the amphibian crisis using only numbers. The 2008 global amphibian assessment lists 120 potentially extinct species and 39 extinct amphibian species. Of these, 94 had chytridiomycosis listed as a likely threat associated with their disappearance. Most of the missing species are from Central and South America, but we are also losing species from North America, the Caribbean, Australia, the Middle East, Asia and Australia.

Now let’s try and put those numbers into the context of our mammal-centric world. Think of a whole bunch of endangered mammals from around the world: a jaguar, Panthera onca, a Baird’s tapir, Tapirus bairdii, the golden lion tamarin, Leontopithecus rosalia, a mountain pygmy possum, Burramys parvus, Dama gazelle, Nanger dama, and the New Guinea big-eared bat, Pharotis imogene. Repeat that exercise 25 times, and you’ll have some idea of what we have probably already lost in the amphibian world.

Here is a roll-call of missing amphibians. Those marked with an (EX) are classified by the IUCN as extinct. Those with an asterisk * next to them have had chytridiomycosis suggested as one of the threats associated with their disappearance.

MISSING FROGS

Alytidae – Midwife Toads

1. Discoglossus nigriventer (EX) Rediscovered in 2011!

Arombatidae

1. Aromobates nocturnus *

2. Mannophryne neblina*

3. Prostherapis dunni*

Bufonidae – True toads

1. Adenomus kandianus (EX)

2. Anaxyrus baxteri (EX in the wild)*

3. Andinophryne colomai

4. Atelopus arthuri*

5. Atelopus balios*

6. Atelopus carbonerensis*

7. Atelopus chiriquiensis*

8. Atelopus chrysocorallus*

9. Atelopus coynei*

10. Atelopus famelicus*

11. Atelopus guanujo*

12. Atelopus halihelos*

13. Atelopus ignescens (EX)*

14. Atelopus longirostris (EX)*

15. Atelopus lozanoi*

16. Atelopus lynchi *

17. Atelopus mindoensis*

18. Atelopus muisca*

19. Atelopus nanay*

20. Atelopus oxyrhynchus*

21. Atelopus pachydermus*

22. Atelopus peruensis*

23. Atelopus pinangoi*

24. Atelopus planispina*

25. Atelopus senex*

26. Atelopus sernai*

27. Atelopus sorianoi*

28. Atelopus vogli

29. Incilius fastidiosus*

30. Incilius holdridgei (EX)*

31. Incilius periglenes (EX)*

32. Melanophryniscus macrogranulosus

33. Nectophrynoides asperginis*

34. Peltophryne fluviatica

35. Rhinella rostrata

Centrolenidae – Glass frogs

1. Centrolene ballux*

2. Centrolene heloderma*

3. Hyalinobatrachium crybetes

Ceratophryidae – Horned frogs

1. Telmatobius cirrhacelis*

2. Telmatobius niger*

3. Telmatobius vellardi*

Cragastoridae

1. Craugastor anciano

2. Craugastor andi*

3. Craugastor angelicus*

4. Craugastor chrysozetetes (EX)*

5. Craugastor coffeus

6. Craugastor cruzi*

7. Craugastor emleni*

8. Craugastor escoces (EX)*

9. Craugastor fecundus*

10. Craugastor fleischmanni*

11. Craugastor guerreroensis*

12. Craugastor merendonensis*

13. Craugastor milesi (EX)**Population just rediscovered in Honduras (see comments)

14. Craugastor olanchano*

15. Craugastor omoaensis*

16. Craugastor polymniae*

17. Craugastor saltuarius*

18. Craugastor stadelmani*

19. Craugastor trachydermus*

Cryptobatrachidae

1. Cryptobatrachus nicefori

Cycloramphidae

1. Cycloramphus ohausi*

2. Odontophrynus moratoi

3. Rhinoderma rufum*

Dendrobatidae – Poison dart frogs

1. Colostethus jacobuspetersi

2. Hyloxalus edwardsi

3. Hyloxalus ruizi

4. Hyloxalus vertebralis*

5. Ranitomeya abdita*

Dicroglossidae

1. Nannophrys guentheri

Eleutherodactylidae – Neotropical frogs

1. Eleutherodactylus eneidae*

2. Eleutherodactylus glanduliferoides

3. Eleutherodactylus jasper*

4. Eleutherodactylus karlschmidti*

5. Eleutherodactylus orcutti*

6. Eleutherodactylus schmidti*

7. Eleutherodactylus semipalmatus*

Hylidae – Treefrogs

1. Bokermannohyla claresignata*

2. Bokermannohyla izecksohni

3. Bromeliohyla dendroscarta*

4. Charadrahyla altipotens*

5. Charadrahyla trux*

6. Ecnomiohyla echinata*

7. Hyla bocourti*

8. Hyloscirtus chlorosteus

9. Hypsiboas cymbalum*

10. Isthmohyla calypso*

11. Isthmohyla debilis*

12. Isthmohyla graceae*

13. Isthmohyla tica*

14. Litoria castanea* Breaking news – this has been rediscovered after 30 years!

15. Litoria lorica*

16. Litoria nyakalensis*

17. Litoria piperata*

18. Megastomatohyla pellita*

19. Plectrohyla calvicollina*

20. Plectrohyla celata*

21. Plectrohyla cembra*

22. Plectrohyla cyanomma*

23. Plectrohyla ephemera*

24. Plectrohyla hazelae*

25. Plectrohyla siopela*

26. Plectrohyla thorectes*

27. Phrynomedusa fimbriata (EX)

28. Scinax heyeri*

Hemiphractidae – Marsupial frogs

1. Gastrotheca lauzuricae

Hylodidae

1. Crossodactylus trachystomus

Leptodactylidae – Southern frogs

1. Paratelmatobius mantiqueira*

Megophryidae – Asian toadfrogs

1. Scutiger maculatus

Myobatrachidae – Australian toadlets and waterfrogs

1. Taudactylus acutirostris*

2. Taudactylus diurnus (EX)*

3. Rheobatrachus silus (EX)*

4. Rheobatrachus vitellinus (EX)*

Petropeptidae

1. Conraua derooi

2. Petropedetes dutoiti*

Ranidae – True frogs

1. Lithobates fisheri (EX)

2. Lithobates omiltemanus*

3. Lithobates pueblae

4. Lithobates tlaloci

Rhacophoridae – Asian Tree Frogs

1. Philautus jacobsoni

2. Philautus adspersus (EX)

3. Philautus dimbullae (EX)

4. Philautus eximius (EX)

5. Philautus extirpo (EX)

6. Philautus halyi (EX)

7. Philautus hypomelas (EX)

8. Philautus leucorhinus (EX)

9. Philautus maia (EX)

10. Philautus malcolmsmithi (EX)

11. Philautus nanus (EX)

12. Philautus nasutus (EX)

13. Philautus oxyrhynchus (EX)

14. Philautus pardus (EX)

15. Philautus rugatus (EX)

16. Philautus stellatus (EX)

17. Philautus temporalis (EX)

18. Philautus travancoricus (EX)

19. Philautus variabilis (EX)

20. Philautus zal (EX)

21. Philautus zimmeri(EX)

Strabomantidae

1. Holoaden bradei

2. Oreobates zongoensis

3. Pristimantis bernali

MISSING SALAMANDERS

Plethodondiade – Lungless salamanders

1. Bradytriton silus

2. Chiropterotriton magnipes

3. Oedipina paucidentata

4. Plethodon ainsworthi (EX)

5. Pseudoeurycea ahuitzotl

6. Pseudoeurycea aquatica

7. Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl

8. Pseudoeurycea praecellens

9. Pseudoeurycea tlahcuiloh

10. Thorius infernalis

11. Thorius narismagnus

Salimandridae – Newts

1. Cynops wolterstorffi (EX)

Have you seen any of these missing amphibians? Do you think that other species should be added? Use the comments field below to tell us your thoughts. For another list of possibly extinct species, grouped by countries, see amphibia web.

Keep an open eye in Panama and you might just see a Panamanian Golden Frog. Local legend used to promise luck to anyone who spotted the frog in the wild and that when the frog died, it would turn into a gold talisman, known as a huaca. Nowadays, you’ll see the frogs on decorative cloth molas made by the Kuna Indians, on T-shirts, as inlaid design on a new overpass in Panama City and even on lottery tickets. In the market at El Valle de Antòn, you will see them by the thousands either as enamel-painted terracotta or on hand-carved tagua nuts. The one place you probably won’t see a Panamanian Golden Frog, however, is in their native home—the crystal clear streams of the ancient volcanic crater of El Valle de Antòn. In the mountain forests you may spot other similar-looking extant species such as Atelopus varius, but the only local and true Panamanian Golden Frogs Atelopus zeteki are those breeding in captivity at the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center (EVACC) at the El Nispero Zoo.

Keep an open eye in Panama and you might just see a Panamanian Golden Frog. Local legend used to promise luck to anyone who spotted the frog in the wild and that when the frog died, it would turn into a gold talisman, known as a huaca. Nowadays, you’ll see the frogs on decorative cloth molas made by the Kuna Indians, on T-shirts, as inlaid design on a new overpass in Panama City and even on lottery tickets. In the market at El Valle de Antòn, you will see them by the thousands either as enamel-painted terracotta or on hand-carved tagua nuts. The one place you probably won’t see a Panamanian Golden Frog, however, is in their native home—the crystal clear streams of the ancient volcanic crater of El Valle de Antòn. In the mountain forests you may spot other similar-looking extant species such as Atelopus varius, but the only local and true Panamanian Golden Frogs Atelopus zeteki are those breeding in captivity at the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center (EVACC) at the El Nispero Zoo. In the early 2000’s conservationists warned that this day-glo yellow emblem of Panama was in grave danger of extinction. In emergency response,

In the early 2000’s conservationists warned that this day-glo yellow emblem of Panama was in grave danger of extinction. In emergency response,  A tragedy has thus been averted. Instead of a dire warning of the future fate of the planet, Panamanian Golden Frogs are now a symbol of hope. Exiled frogs are playing the role of a flagship species, bringing the story of global amphibian declines to world wide audiences in zoos and aquaria, magazines and films. As the logo of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, the Panamanian Golden Frog is a powerful symbol uniting

A tragedy has thus been averted. Instead of a dire warning of the future fate of the planet, Panamanian Golden Frogs are now a symbol of hope. Exiled frogs are playing the role of a flagship species, bringing the story of global amphibian declines to world wide audiences in zoos and aquaria, magazines and films. As the logo of the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, the Panamanian Golden Frog is a powerful symbol uniting  It’s difficult to communicate the extent of the amphibian crisis using only numbers. The 2008 global amphibian assessment lists 120 potentially extinct species and 39 extinct amphibian species. Of these, 94 had chytridiomycosis listed as a likely threat associated with their disappearance. Most of the missing species are from Central and South America, but we are also losing species from North America, the Caribbean, Australia, the Middle East, Asia and Australia.

It’s difficult to communicate the extent of the amphibian crisis using only numbers. The 2008 global amphibian assessment lists 120 potentially extinct species and 39 extinct amphibian species. Of these, 94 had chytridiomycosis listed as a likely threat associated with their disappearance. Most of the missing species are from Central and South America, but we are also losing species from North America, the Caribbean, Australia, the Middle East, Asia and Australia.