Before beginning my research at the Smithsonian, I knew surprisingly little about the status of the world’s amphibians. I was fortunate to be awarded an internship through Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine based at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, VA. Once I arrived in Front Royal, I learned quickly about the plight of amphibians around the globe and I remember listening in awe when I was first told about the Amphibian Arks in Gamboa and El Valle in Panama and how they hold the last remaining individuals of some of Panama’s most precious amphibian species. They had been brought into these assurance colonies because of the threat of a devastating fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) that is responsible for the disappearance of many species around the world. Initially, the harlequin frogs in the Amphibian Arks in Panama were housed individually, because when placed together keepers observed that males would fight and they were worried the fighting would unduly stress these precious animals. However, this quickly led to a space shortage as the amphibian ark filled up. The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, which helps coordinate the Species Survival Plan for Panamanian Golden frogs in the USA, suggested that we group the animals together in same-sex groups. They noted that this was working out just fine for frogs reared in captivity, but we wanted to evaluate whether wild-collected harlequin frogs would adapt to this group-housing situation.

Before beginning my research at the Smithsonian, I knew surprisingly little about the status of the world’s amphibians. I was fortunate to be awarded an internship through Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine based at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, VA. Once I arrived in Front Royal, I learned quickly about the plight of amphibians around the globe and I remember listening in awe when I was first told about the Amphibian Arks in Gamboa and El Valle in Panama and how they hold the last remaining individuals of some of Panama’s most precious amphibian species. They had been brought into these assurance colonies because of the threat of a devastating fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) that is responsible for the disappearance of many species around the world. Initially, the harlequin frogs in the Amphibian Arks in Panama were housed individually, because when placed together keepers observed that males would fight and they were worried the fighting would unduly stress these precious animals. However, this quickly led to a space shortage as the amphibian ark filled up. The Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, which helps coordinate the Species Survival Plan for Panamanian Golden frogs in the USA, suggested that we group the animals together in same-sex groups. They noted that this was working out just fine for frogs reared in captivity, but we wanted to evaluate whether wild-collected harlequin frogs would adapt to this group-housing situation.

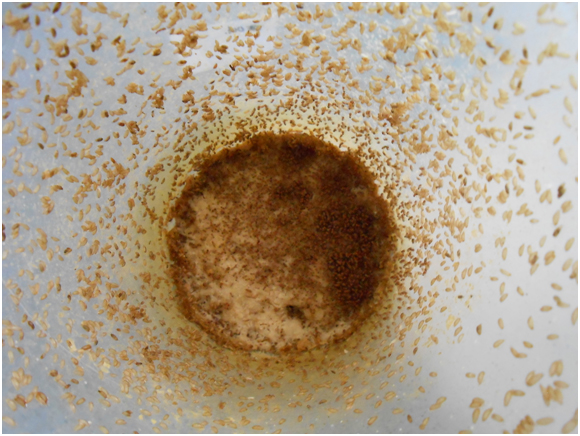

My collaborators in Panama conducted a behavioral study of frogs placed in groups and monitored the number of aggressive interactions between the frogs, making sure that there were no injuries. Back in Front Royal, I worked with my colleagues in the endocrine labs to measure the amount of cortisol, a steroid hormone that the frog produces and can be detected in its poop. We did this by adapting existing stress hormone monitoring methods that the SCBI uses for many other wildlife species, like pandas and elephants. We found that, initially, the frogs housed together would interact aggressively towards one another. This aggression was mirrored by an elevation in stress hormones in the feces during the first week of the study. However, after the first 2 weeks, the frequency of aggressive behaviors declined dramatically, and the concentration of cortisol dropped back down to normal. Based on these results, we determined that wild caught harlequin frogs could be safely housed together in same-sex groups over the longer term, and this study helped us to greatly reduce space constraints in our ex-situ collection of amphibians. We hope that our new method may be useful to others wanting to evaluate husbandry issues in captive amphibian collections. Read the full paper in PLoS One here By Shawna Cikanek, Kansas State University