Panama Amphibian Conservation Timeline

1989 – Martha Crump makes the last sighting of the charismatic MonteVerde Golden toad from a National Park in Costa Rica, having noted a sudden population crash from 1,500 individuals in 1987.

1989 – Martha Crump makes the last sighting of the charismatic MonteVerde Golden toad from a National Park in Costa Rica, having noted a sudden population crash from 1,500 individuals in 1987.

1991 – The Declining Amphibian Population Taskforce established by the Species Survival Commission (SSC) to investigate mysterious amphibian disappearances from around the World.

1998 – Scientists note that a fungus is associated with amphibian mortality events in Australia and Central America.

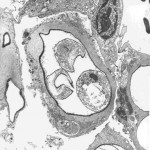

1999 – Scientists from the National Zoo and The University of Maine describe and name a new amphibian fungal disease and name it Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), proving through Koch’s postulates that it is a deadly agent of disease.

1999 – Scientists from the National Zoo and The University of Maine describe and name a new amphibian fungal disease and name it Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), proving through Koch’s postulates that it is a deadly agent of disease.

2000 – The Baltimore Zoo received approval to import and establish a captive population of adult Panamanian golden frogs (Atelopus zeteki) under Project Golden Frog.

2004 – Karen Lips and colleagues noted the westward spread of Bd through Central America and within 5 months of arriving at El Cope, they found that Bd extirpated 50% of species and 80% of individuals.

2005 – US zoos concerned about the potential extinction of amphibians in the El Valle region conduct a rescue operation to established assurance colonies of 15 species of amphibian at Zoo Atlanta and Atlanta Botanical Gardens. Houston Zoo begins planning to build an in-country breeding facility to be called the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center (EVACC).

2005 – US zoos concerned about the potential extinction of amphibians in the El Valle region conduct a rescue operation to established assurance colonies of 15 species of amphibian at Zoo Atlanta and Atlanta Botanical Gardens. Houston Zoo begins planning to build an in-country breeding facility to be called the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center (EVACC).

2006 – As predicted, Bd arrived in El Valle de Anton, home of the Panamanian Golden frog, but the EVACC center was not yet complete, but rescue operations were conducted, temporarily housing rescued amphibians in the Hotel Campestre.

2007 – First amphibians are transferred to the EVACC center set up by the Houston Zoo and other partners.

Bd is found east of the Panama Canal for the first time, prompting calls for establishment of Ex-situ facilities to be developed to rescue 25-50 amphibians at risk of extinction in Eastern Panama.

Bd is found east of the Panama Canal for the first time, prompting calls for establishment of Ex-situ facilities to be developed to rescue 25-50 amphibians at risk of extinction in Eastern Panama.

2008 – Project golden frog has 1,500 captive individuals representing 41 wild-caught animals in US Zoos and aquaria, but the golden frog is now probably extinct in the wild.

2009 – Reid Harris and colleagues publish their findings showing that certain bacteria can be grown of Mountain Yellow-Legged Frogs and protect them from Bd.

2009 – The MOU establishing the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is signed as a joint partnership between the Houston Zoo (who established EVACC) and the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Africam Safari, Zoo New England, Summit Municipal Park, Defenders of Wildlife, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. Panamanian Herpetologist Dr. Roberto Ibáñez was appointed as the project director, and Dr. Brian Gratwicke was appointed as the lead scientist.The Project consisted of three distinct and complementary parts: 1) the ongoing operation of EVACC by the Houston Zoo, 2) searching for a cure for the amphibian chytrid fungus, 3) the construction of a second Amphibian Rescue Center to expand in-country capacity for rescued frogs.

2009 – The MOU establishing the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is signed as a joint partnership between the Houston Zoo (who established EVACC) and the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Africam Safari, Zoo New England, Summit Municipal Park, Defenders of Wildlife, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. Panamanian Herpetologist Dr. Roberto Ibáñez was appointed as the project director, and Dr. Brian Gratwicke was appointed as the lead scientist.The Project consisted of three distinct and complementary parts: 1) the ongoing operation of EVACC by the Houston Zoo, 2) searching for a cure for the amphibian chytrid fungus, 3) the construction of a second Amphibian Rescue Center to expand in-country capacity for rescued frogs.

2009 – The Panamanian government passes legislation mandating the conservation of amphibians and recognizing the importance of amphibians in Panama.

2010 – A Golden Frog Law is passed recognizing August 14 as national golden frog day.

2011 – The first annual golden frog day festival is held in El Valle de Anton.

2012 – ANAM (now Miambiente) publishes a national amphibian conservation action plan for Panama.

Project Atelopus is started to search for any surviving golden frogs in Western Panama. The team found some surviving Atelopus varius but no Atelopus zeteki.

2013 – A stakeholder meeting is held in El Valle de Anton to map out a long-term plan for the conservation of golden frogs.

2014 – The “Fabulous frogs of Panama” Exhibit opens at the Punta Culebra nature Center in Amador, Panama City.

2014 – The “Fabulous frogs of Panama” Exhibit opens at the Punta Culebra nature Center in Amador, Panama City.

2015 – The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project facility is officially opened at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Gamboa Field station, and the MOU establishing the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project is renewed between the Houston Zoo, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Zoo New England, STRI and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, with STRI assuming management responsibilities for both EVACC and the Gamboa ARCC.

2017 – The first release trials of captive-bred Atelopus limosus are conducted in the Mamoni Valley Preserve.

2017 – The first release trials of captive-bred Atelopus limosus are conducted in the Mamoni Valley Preserve.

2018 – The first release trails of Atelopus varius are conducted at a Cobre Panama site in the Donoso Area.

2019 – The amphibian conservation facility at the Nispero Zoo (previously known as EVACC) is closed. Custodianship of the living collection of animals housed there is split between the PARC project in Gamboa and the newly formed non-profit EVACC foundation that continues to operate independently in El Valle de Anton.

2021 – The Atelopus Survival Initiative is formed to implement a conservation plan to conserve harlequin toads throughout latin America.