The golden frogs were given a bath in one of four probiotic solutions. (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

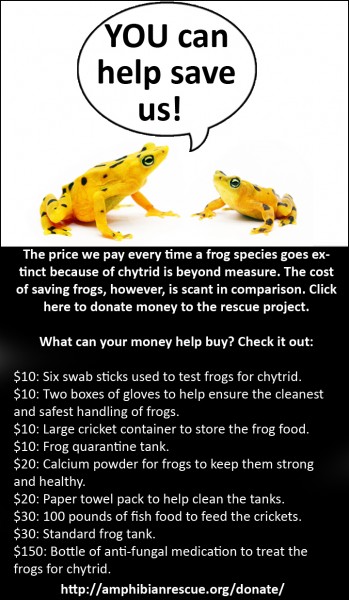

We usually think of bacteria as bad for us, but that isn’t always the case. For us humans, the most common examples of helpful bacteria, or probiotics, live in yogurt. Now, scientists believe amphibian probiotics may be the key to fighting chytridiomycosis, the fungal disease devastating frogs around the world.

A few years ago, Reid Harris, a biology professor at James Madison University, discovered that local salamanders that could survive chytrid played host to bacteria in their skin. Now, Brian Gratwicke, a research biologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, is collaborating with a team from Virginia Tech, James Madison, Villanova and Vanderbilt Universities in an experiment to see if similar bacteria can protect the Panamanian golden frog, which he calls “the poster-child for amphibian conservation.”

The first step is to find a probiotic that will stick to the golden frogs. In early December, the team began giving golden frogs baths using four different types of bacteria. Researchers gathered the potential probiotics from frogs in Panama in 2009. The finalists were chosen based on their ability to prevent chytrid growth in lab tests, with a preference for bacteria that are common in close relatives of Panamanian golden frogs.

Every two weeks, each frog is swabbed to check whether its probiotic has made itself at home. The tests take some time, so a month and a half in, the team is still waiting for results to see which probiotics are sticking. But they do have some good news already.

“The bacteria haven’t been causing any problems with the frogs and they all look healthy,” said Gratwicke, who emphasizes how important it is to use only beneficial bacteria. In addition to tracking weight gain and other visible characteristics, Shawna Cikanek, a student at Kansas State College of Veterinary Medicine is using frog poop to study stress hormones to get a better picture of the animals’ overall health and whether the bacteria are causing any stress.

“The bacteria haven’t been causing any problems with the frogs and they all look healthy,” said Gratwicke, who emphasizes how important it is to use only beneficial bacteria. In addition to tracking weight gain and other visible characteristics, Shawna Cikanek, a student at Kansas State College of Veterinary Medicine is using frog poop to study stress hormones to get a better picture of the animals’ overall health and whether the bacteria are causing any stress.

The probiotics that stick to the frogs for a full three months will move on to the next round of tests, when bacteria-shielded frogs will be infected with chytrid to check for any adverse effects.

“Hopefully, the bacteria are going to do their thing and protect these little guys,” said Matt Becker, a PhD candidate from Virginia Tech who is conducting the experiment. Whatever probiotics make the cut will be tested again on golden frogs bred in Panama before scientists develop a final plan.

So far, chytrid has defied attempts to stop it. Scientists may be able to selectively breed frogs resistant to chytrid, but there has been very little work done so far in that direction. But there are high hopes for probiotics’ potential to protect frogs. “It’s a long shot, but it’s our best shot,” said Gratwicke.

Becker hopes that one day, probiotics will allow Panamanian golden frogs to return to their homes. “These guys are really neat and it’s so sad not to see them in the wild,” he said. “We have a moral obligation since indicators are pointing to humans as major spreaders of the disease through the frog trade.”

—Meghan Bartels, Smithsonian’s National Zoo