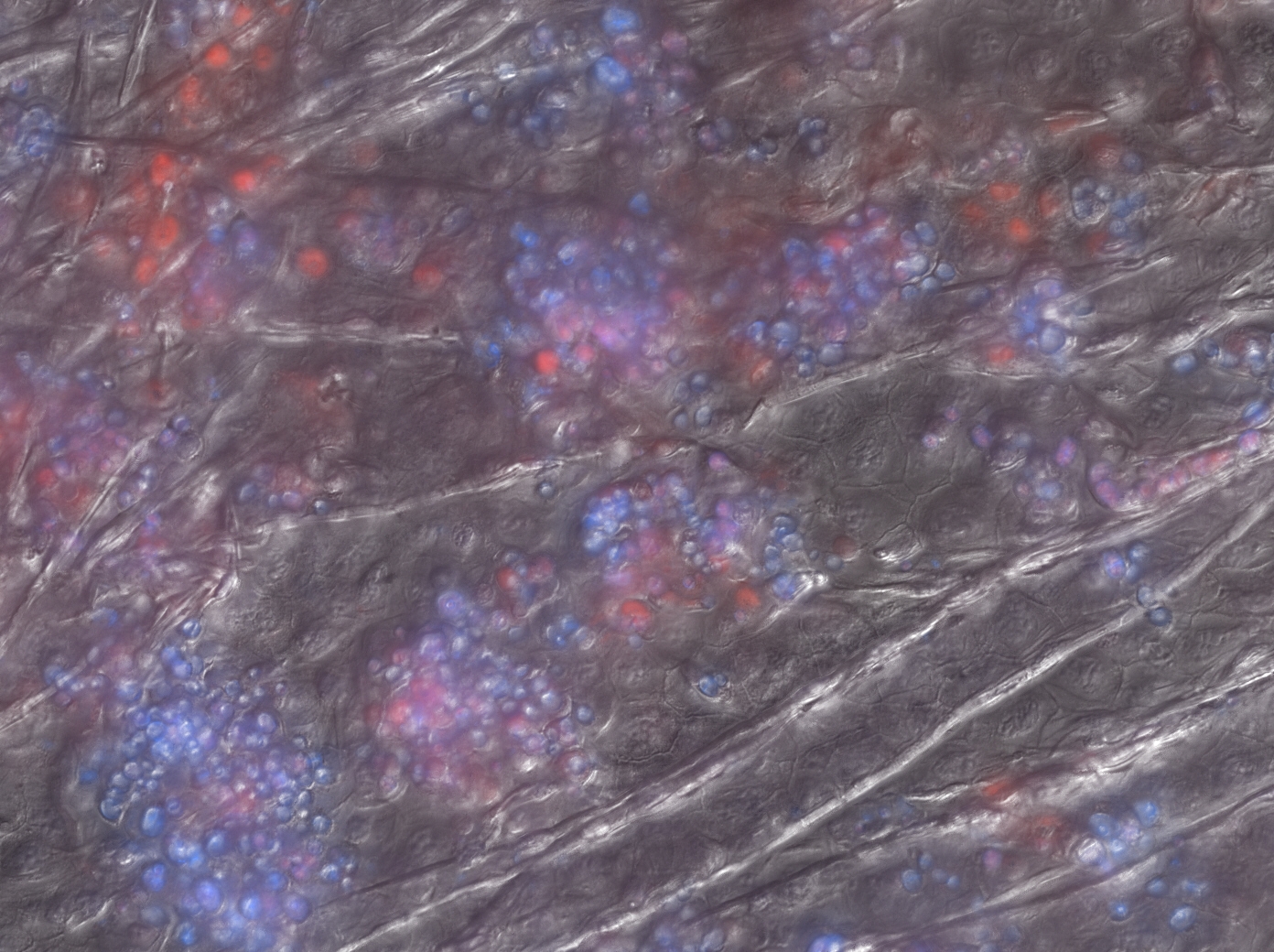

As the fungal disease, chytridiomycosis, wipes out frogs and other amphibians across Panama, snakes appear to be more common than previously—but are they really, and will they last?

Chad Montgomery took this photo of an eyelash viper, Bothriechis schleglii, eating a frog in El Cope, Panama, one of the most studied frog decline sites here.

Panama’s ongoing “Amphibian Armageddon” completely changes who eats whom—aka the food chain—near the highland tropical streams where frogs and amphibians used to abound.

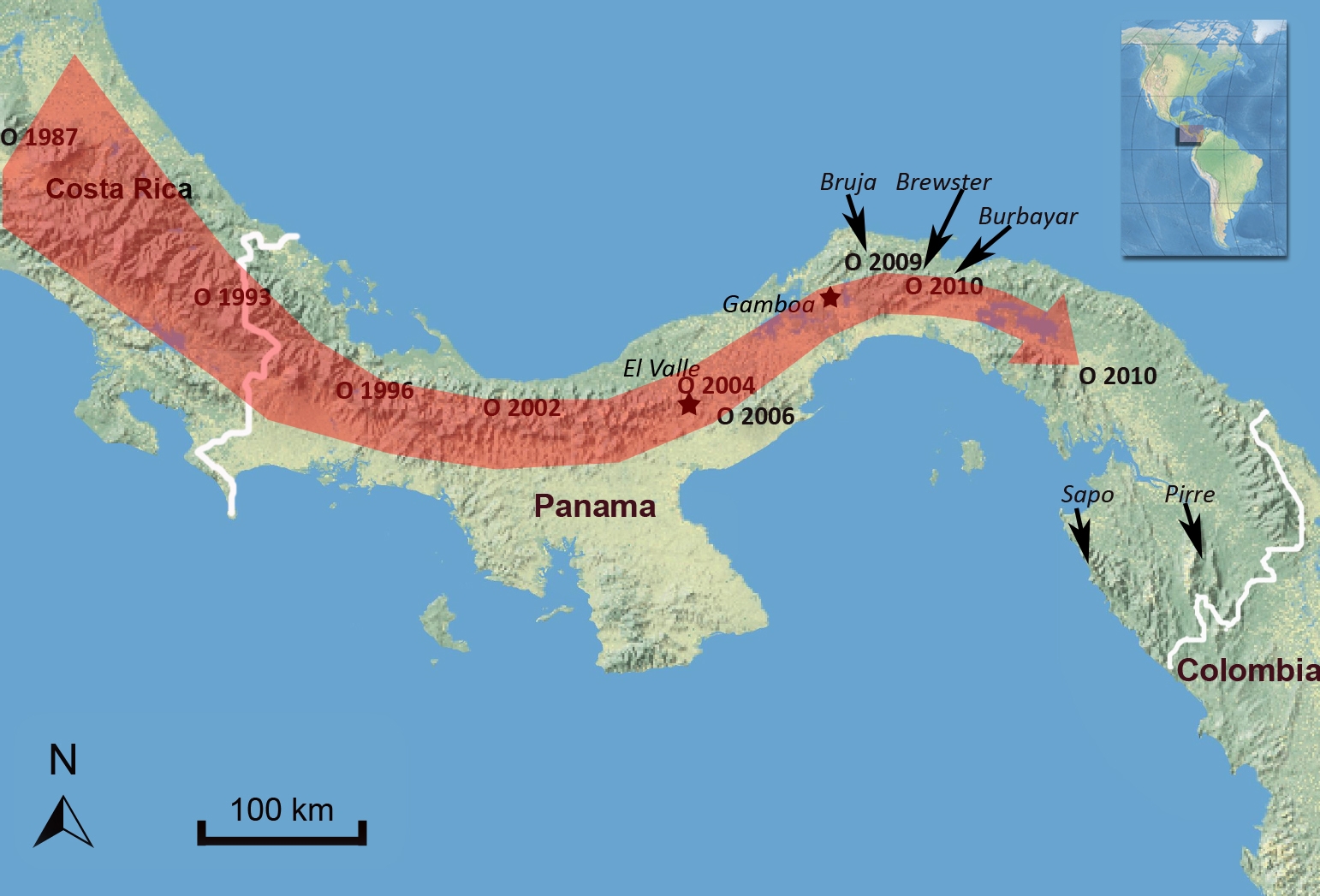

Researchers from the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project’s latest expedition to Cerro Brewster in Central Panama report that where the frogs used to be, they are now seeing snakes—deadly eyelash vipers, to be exact.

This weekend my family was visiting from the United States and we ventured out on my favorite easy day trip from Panama City–a drive up to El Valle, a little town nestled in the crater of an extinct volcano.

Our first stop was El Nispero, a small private zoo, home to the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, EVACC, a project initiated by the Houston Zoo with some logistical support from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

EVACC is housed in a new building—with a beautiful small exhibit about Panama’s endangered frogs where you can see one of the last remaining golden frogs, Atelopus zeteki—named for James Zetek, one of the founder’s of STRI’s Barro Colorado Island research station in the 1920’s.

Edgardo Griffith is pretty much the powerhouse behind EVACC. He was in the lab there and was kind enough to take a break to talk to me about the most recent rescue project trip up to Brewster Hill.

The last visit to Brewster, which also included a big group of people from the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo in Colorado, was in November, 2009. That team found a lot of frogs, but many of them were already infected with the fungus.

This time they found very few frogs, although they were psyched to have found a female Altelopus limosus, the Limosa harlequin frog, which the rescue project recently bred in captivity.

Instead they found a lot of snakes. Edgardo speculated that because there are fewer frogs it is not so much that there are more snakes, but that the snakes have to work harder to find frogs and are concentrated around the streams where a few frogs remain, so the team was just running into them more often. But without more careful work, it is hard to say.

Chad Montgomery, now a professor at Truman State University in Missouri, did his post-doctoral research with Karen Lips from the University of Maryland on the effects of amphibian declines on frog predators at El Cope, one of the most studied frog decline sites in Panama.

He told me: “In 2005, the first year following the amphibian decline, we saw a change in the snake community, with snake species that are more dependent on amphibians as food (such as Sibon and Leptodeira) becoming less common relative to those snake species that are not as reliant on amphibians as prey (such as Oxybelis and Dipsas).”

“The ecosystem can’t support the previously large snake community,” he said. “Ultimately, loss of amphibians probably causes local extinction of some snake species and severely reduced population sizes in those species that remain.”

According to Julie Ray, the director of the La Mica Biological Station in El Cope, it’s unusual to see so many eyelash vipers, which have declined in El Cope following the frog decline. Eyelash vipers feed on frogs, lizards, mice, etc. She also said that Fer de lance, Panama’s most poisonous snake, actually feed on dying and dead frogs.

One of the truths that the rescue project reveals is how little we still know about playing Noah. Many of Panama’s endangered frogs have never been studied in the wild or kept in captivity.

Not only do rescue project researchers have to figure out what frogs eat and what they need to survive and reproduce in a zoo, they still have no idea how their habitat will change as a result of the disease and when, if ever, it will be possible to reintroduce captive frogs back into the wild. We need to know much more about how frog extinctions change insect and animal communities…and that take precious time and money, which is why frog rescue projects need your support.

–Beth King, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute